Information

Complete title: The Cartoon Exhibition

Curator: Henri Langlois

Set Designers: Jacques Douy & Jean Castanier

Dates: February 7, 1946 – ?

Location: 7, avenue de Messine, Paris, then Brussels, Belgium

Country: France

Opening hours: from 11am until 10pm

Back to Exhibitions

The French Cinemathèque

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Henri Langlois, the legendary administrator of the Cinémathèque Française, which he had helped found 10 years earlier, organized exhibitions at the Cinémathèque at 7 avenue de Messine, 75008 Paris. The first two were closely linked and opened on February 7, 1946. If the newspaper Combat is to be believed, the electricians were still busy that day, as the installations had not yet been finalized. The first exhibition was entitled “The Cartoon Exhibition”, and the second was dedicated to Émile Reynaud, considered the precursor of animated cartoons. For the occasion, his son presented his father’s films on a newly-built machine, necessary for their projection, the two “theaters” owned by Émile having been destroyed by their creator.

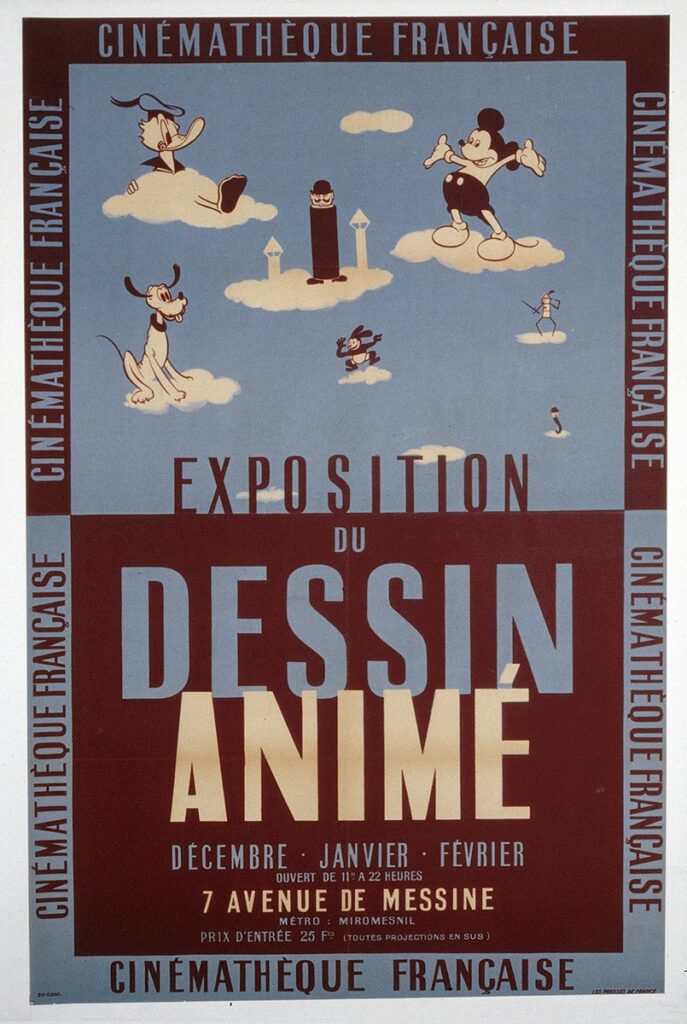

In this exhibition, the rare animated feature films already released, and those still in the making, are given pride of place. Naturally, Snow White is among them. Surprisingly, the exhibition poster advertises the months of December to February, whereas the exhibition only opens in February, with opening hours from 11am to 10pm. However, the press reports opening times of 10am to 7pm.

It seems that the exhibition was then exported to Brussels at the end of 1946.

P. Robin’s article in La Cinématographie Française of February 23, 1946 describes the exhibition. Here is the text.

The Cinémathèque Française has opened two brilliant exhibitions devoted to Émile Reynaud and cartoons.

Two very interesting exhibitions have opened at the Cinémathèque Française, 7, avenue de Messine: ” The Cartoon Exhibition ” and ” The Emile Reynaud Exhibition “. Both complement each other, since before cinema existed, Emile Reynaud had literally invented the “Dessin Animé” (Cartoon) with his “Praxinoscope”.

From Reynaud to Grimault, via Cohl and Disney, the Exhibition in general presents us with a synthesis of this little-known art form, which enthrals and delights young and old alike.

As soon as we enter, we’re greeted by all the characters we know. Here’s Popeye and his wife, life-size – if I dare say so – in a dramatic situation and under the placid eye of a big fish, hero of a charming Disney film, while, sulking, in a corner, Donald, the eternally unlucky, ponders his misfortunes. On the left, Mickey, Minnie, Goofy, Bonzo, Pinocchio and Pluto are gracefully arranged in checkerboard cubes. On the right, in a display case, are the ancestors, the “Phénakisticope” discs and the magic lantern.

As we begin our visit, we see a descriptive and explanatory table of the cartooning technique itself: Grimault’s studies for his next film, photos of workshops for tracing, painting, animation, etc., etc., right through to the complete shooting and realization (1). Above a display case containing Alexief’s pin board is an original Disney study for “Fantasia“.

The Cohl room retraces the life and work of the precursor of cartooning, who created all types of animation: anecdotal drawings, puppet films, shadow puppets, abstract films, advertising films and educational yarns. Numerous photos and drawings illustrate all these works. We then enter the retrospective room, where photos of the most important cartoon films since their origins are on display: Mac Kay’s Gertie the Dinosaur (1908), Pat Sullivan’s Felix the Cat (1913). Paul Terry’s Kingdom of Air (1915), Disney’s Skeleton Dance (1929), The Tale About Czar Durundai (1934), Snow White (1937), Pinocchio (1938). Gulliver (1939). Fantasia (1940), Victory Through Air Power (1942), etc., etc.

In an adjacent room, like a scene from the Grévin Wax Museum, here’s a recreation of the big scene from Painlevé’s Bluebeard, using puppets from the film, and then the carriage used by Jean Perdrix to animate the song of the same name. There are also films by Len Lye, Fischinger’s emulator, photos by AIexieff, Lotte Reininger and more…

The highlight of the exhibition, however, is Jacques Damiot’s presentation of Starevitch’s puppets, including the Fox, the Cicada and the Ant, the Frog, the Lion, etc., skilfully arranged and full of life.

Opposite, a panel is reserved for French Cartoons: Arcady, Grimault, Image etc., etc., with documents displayed in their most cheerful tricolor ensemble.

Finally, as no exhibition on cinema would be complete without film screenings, the Cinémathèque’s small auditorium features a selection of cartoons, including a rhythmic film of Fishinger, a film by Paul Grimault, and two Mickeys, one of which, Building a Building, is a masterpiece of rhythm and comicality.

The Emile Reynaud exhibition on the second floor of the Avenue de Messine showcases the work of cinema’s precursors. The Zootrope, the Thaumatrope, the Phakinescope (a plagiarism of Reynaud’s) and, above all, Reynaud’s own inventions, the Praxinoscope and Photo-scénographe, are on display in a very 19th-century setting. But the most beautiful piece on display is undoubtedly the tape “Pauvre Pierrot”, which was screened at the Maison de la Chimie for the Cinquantenaire. This is one of the most precious documents we currently possess on the origins of optical theater, and we owe it to the kindness of the Musée des Arts et Métiers to see it. The other documents are on loan from the inventor’s sons, Paul and André Reynaud.

To conclude, we reproduce the text affixed to the entrance to these exhibitions, which we feel best sums up the impression this visit made on us:

“Realized before the Cinema by Emile Reynaud, brought to the screen by S. Blakeston, the cartoon seems to have arrived in 1945 with Technicolor feature films at the last stage of a formula of which Disney preceded by Pat Sullivan and Fleisher followed by Ub Irweks and Harman and Ising is the most eminent representative. The U.S.S.R. and France are looking for a new formula by talking about Emile Cohl.”

It only remains for us to congratulate those who were able to interest us so well: set designers Jacques Douy and Jean Castanier and the staff of the Cinémathèque, all under the direction of Henri Langlois.

P. Robin.

(1) Incidentally, Walt Disney’s The Reluctant Dragon will also take us on a moving-picture tour of the various pavilions at Burbank Studios, where we’ll be able to see a cartoon film being made.

French Newsreel from March 8, 1946

On its website, the Institut national de l’audiovisuel offers an excerpt from the March 8, 1946 newsreel dealing with this exhibition.