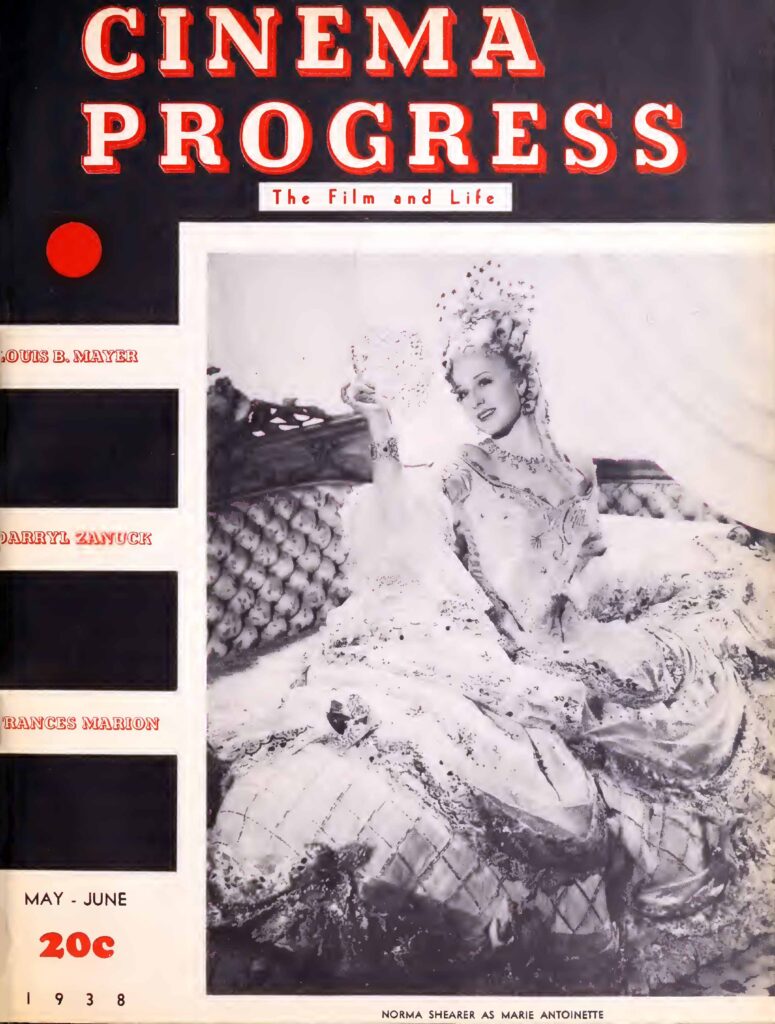

Cinema Progress – The Film and Life is an American magazine. The May-June 1938 (volume 3, number 2) issue shows Norma Shearer as Marie Antoinette on the cover and was sold 20 cents.

On page 14, an article called Cooperative Imagination by Boris V. Morkovin, the editor of the magazine, describes the making of the film.

Cooperative Imagination

Being a further revelation of the technical problems encountered in the making of Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

By Boris V. Morkovin

Fifteen years ago a struggling American youth tried hard to sell his first animated cartoon comedy, “Alice.” Scarcely anybody at that time could divine in the heap of ingenious drawings a foreshadow of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” the ink-pot drama which has started a new epoch in the history of graphic cinema.

From a single-handed draftsman, Walt Disney has developed into a conductor of some sort of polyexpressive optical and acoustical orchestra. Under his inspirational guidance 600 enthusiastic young men and women have been orchestrating cinematic pantomime and color with the music of voice, instruments and sound into harmony, rhythm, and drama.

The huge work of co-operative imagination of writers, artists, animators and composers, which resulted in “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” was achieved with an exactness, a minute division of labor, and the strict organization of a highly mechanized industry. And yet this mechanism was permeated, kindled and moved by the afflatus of the visionary maestro, Walt Disney.

The story was adapted and then re-adapted from Disney’s conception and told visually in preliminary sketch highlights; dialogue and song lyrics were worked out by different writers; each promising “gag” situation, such as Snow White’s renovation of the dwarf’s home, with the assistance of animals and birds, and the washing of the dwarfs, were given over to special gag writers; hundreds of suggestions for details, gags, characterizations, and incidents, including minutia of clothes and background, were added by other workers. All these mass contributions were guided by the spirit of situations and characters which had been established previously in conferences with Disney and checked up by his directors. The five sequences were assigned to five unit directors whose work was co-ordinated again by the supervising director, who served as the immediate interpreter and collaborator of Walt Disney.

Unity of vision and consistency of details were achieved by continuous conferences, with sketches popping up and down on the board. The pantomime, gestures, voice and movement of characters were impersonated by members of the conference and were reinforced by the composer at the piano, who presented his version.

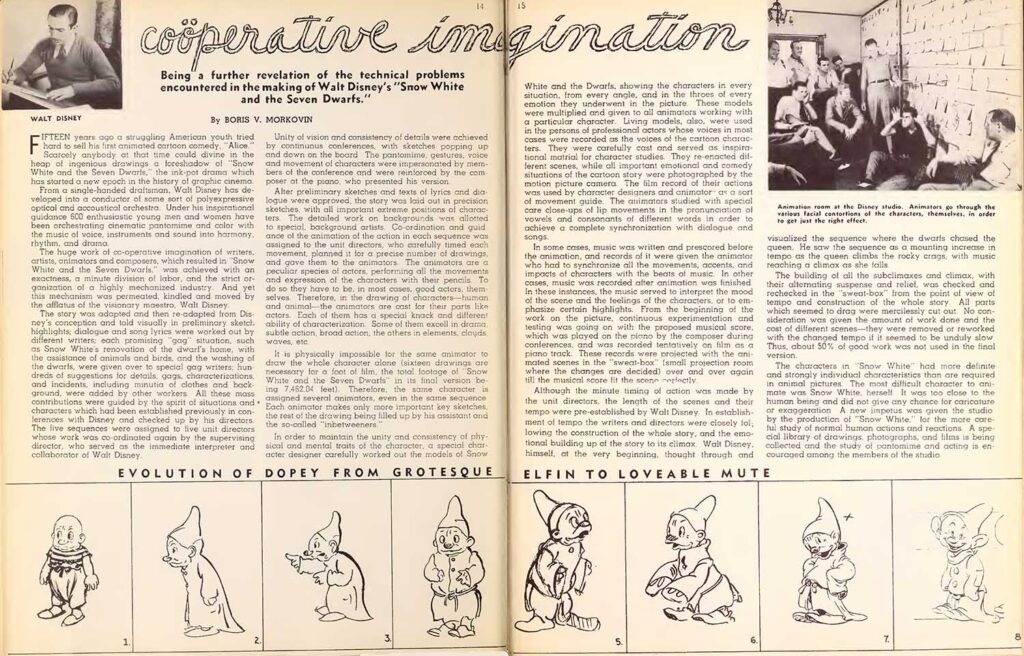

After preliminary sketches and texts of lyrics and dialogue were approved, the story was laid out in precision sketches, with all important extreme positions of characters. The detailed work on backgrounds was allotted to special, background artists. Co-ordination and guidance of the animation of the action in each sequence was assigned to the unit directors, who carefully timed each movement, planned it for a precise number of drawings, and gave them to the animators. The animators are a peculiar species of actors, performing all the movements and expression of the characters with their pencils. To do so they have to be, in most cases, good actors, themselves. Therefore, in the drawing of characters—human and animal—the animators are cast for their parts like actors. Each of them has a special knack and different ability of characterization. Some of them excell in drama, subtle action, broad action, the others in elements, clouds, waves, etc.

It is physically impossible for the same animator to draw the whole character alone (sixteen drawings are necessary for a foot of film, the total footage of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” in its final version being 7,462.04 feet). Therefore, the same character is assigned several animators, even in the same sequence Each animator makes only more important key sketches, the rest of the drawing being filled up by his assistant and the so-called “inbetweeners.”

In order to maintain the unity and consistency of physical and mental traits of the character, a special character designer carefully worked out the models of Snow White and the dwarfs, showing the characters in every situation, from every angle, and in the throes of every emotion they underwent in the picture. These models were multiplied and given to all animators working with a particular character. Living models, also, were used in the persons of professional actors whose voices in most cases were recorded as the voices of the cartoon characters. They were carefully cast and served as inspirational matrial for character studies. They re-enacted different scenes, while all important emotional and comedy situations of the cartoon story were photographed by the motion picture camera. The film record of their actions was used by character designers and animators as a sort of movement guide. The animators studied with special care close-ups of lip movements in the pronunciation of vowels and consonants of different words in order to achieve a complete synchronization with dialogue and songs.

In some cases, music was written and prescored before the animation, and records of it were given the animator who had to synchronize all the movements, accents, and impacts of characters with the beats of music. In other cases, music was recorded after animation was finished. In these instances, the music served to interpret the mood of the scene and the feelings of the characters, or to emphasize certain highlights. From the beginning of the work on the picture, continuous experimentation and testing was going on with the proposed musical score, which was played on the piano by the composer during conferences, and was recorded tentatively on film as a piano track. These records were projected with the animated scenes in the “sweat-box” (small projection room where the changes are decided) over and over again till the musical score fit the scene perfectly.

Although the minute timing of action was made by the unit directors, the length of the scenes and their tempo were pre-established by Walt Disney. In establishment of tempo the writers and directors were closely following the construction of the whole story, and the emotional building up of the story to its climax. Walt Disney, himself, at the very beginning, thought through and visualized the sequence where the dwarfs chased the queen. He saw the sequence as a mounting increase in tempo as the queen climbs the rocky crags, with music reaching a climax as she falls.

The building of all the subclimaxes and climax, with their alternating suspense and relief, was checked and rechecked in the “sweat-box” from the point of view of tempo and construction of the whole story. All parts which seemed to drag were mercilessly cut out. No consideration was given the amount of work done and the cost of different scenes—they were removed or reworked with the changed tempo if it seemed to be unduly slow. Thus, about 5O% of good work was not used in the final version.

The characters in ”Snow White” had more definite and strongly individual characteristics than are required in animal pictures. The most difficult character to animate was Snow White, herself. It was too close to the human being and did not give any chance for caricature or exaggeration A new impetus was given the studio by the production of “Snow White,” for the more careful study of normal human actions and reactions, A special library of drawings, photographs, and films is being collected and the study of pantomime and acting is encouraged among the members of the studio.