November 26, 1938

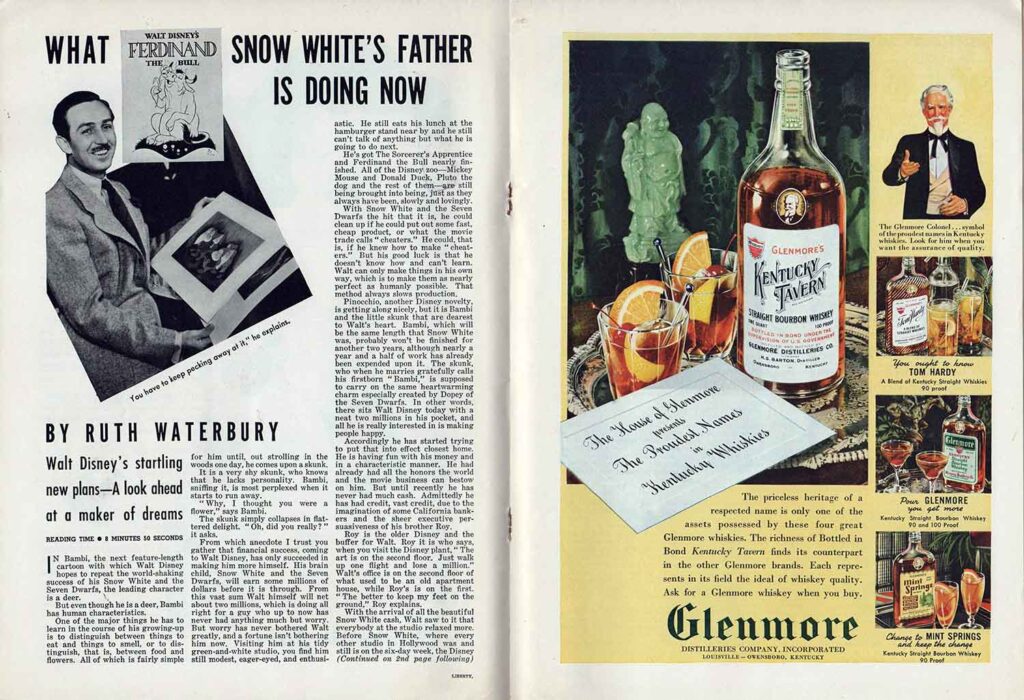

On its cover, the November 26, 1938 issue of Liberty magazine featured an article by Ruth Waterbury entitled “What Snow White’s Father is Doing Now”. The article reviews the producer’s plans following the worldwide success of Snow White. The article is spread over two pages, separated by an advertisement. It discusses Bambi, Pinocchio, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice and unrealized segments of what was to become Fantasia, illustrated by a drawing of Ferdinand the Bull.

What Snow White’s Father is Doing Now

Ruth Waterbury

Walt Disney’s startling new plans – A look ahead at a maker of dreams.

In Bambi, the next feature-length cartoon with which Walt Disney hopes to repeat the world-shaking success of his Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the leading character is a deer. But even though he is a deer, Bambi has human characteristics.

One of the major things he has to learn in the course of his growing-up is to distinguish between things to eat and things to smell, or to distinguish, that is, between food and flowers. All of which is fairly simple for him until, out strolling in the woods one day, he comes upon a skunk. It is a very shy skunk, who knows that he lacks personality. Bambi, sniffing it, is most perplexed when it starts to run away.

” Why, I thought you were a flower,” says Bambi.

The skunk simply collapses in flattered delight. ” Oh, did you really? ” it asks.

From which anecdote I trust you gather that financial success, coming to Walt Disney, has only succeeded in making him more himself. His brain child, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, will earn some millions of dollars before it is through. From this vast sum Walt himself will net about two millions, which is doing all right for a guy who up to now has never had anything much but worry. But worry has never bothered Walt greatly, and a fortune isn’t bothering him now. Visiting him at his tidy green-and-white studio, you find him still modest, eager-eyed, and enthusiastic. He still eats his lunch at the hamburger stand near by and he still can’t talk of anything but what he is going to do next.

He’s got The Sorcerer’s Apprentice and Ferdinand the Bull nearly finished. All of the Disney zoo—Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, Pluto the dog and the rest of them—are still being brought into being, just as they always have been, slowly and lovingly.

With Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs the hit that it is, he could clean up if he could put out some fast, cheap product, or what the movie trade calls ” cheaters.” He could, that is, if he knew how to make ” cheaters.” But his good luck is that he doesn’t know how and can’t learn. Walt can only make things in his own way, which is to make them as nearly perfect as humanly possible. That method always slows production.

Pinocchio, another Disney novelty, is getting along nicely, but it is Bambi and the little skunk that are dearest to Walt’s heart. Bambi, which will be the same length that Snow White was, probably won’t be finished for another two years, although nearly a year and a half of work has already been expended upon it. The skunk, who when he marries gratefully calls his firstborn ” Bambi,” is supposed to carry on the same heartwarming charm especially created by Dopey of the Seven Dwarfs. In other words, there sits Walt Disney today with a neat two millions in his pocket, and all he is really interested in is making people happy.

Accordingly he has started trying to put that into effect closest home. He is having fun with his money and in a characteristic manner. He had already had all the honors the world and the movie business can bestow on him. But until recently he has never had much cash. Admittedly he has had credit, vast credit, due to the imagination of some California bankers and the sheer executive persuasiveness of his brother Roy.

Roy is the older Disney and the buffer for Walt. Roy it is who says, when you visit the Disney plant, ” The art is on the second floor. Just walk up one flight and lose a million.” Walt’s office is on the second floor of what used to be an old apartment house, while Roy’s is on the first. ” The better to keep my feet on the ground,” Roy explains.

With the arrival of all the beautiful Snow White cash, Walt saw to it that everybody at the studio relaxed more. Before Snow White, where every other studio in Hollywood was and still is on the six-day week, the Disney studio worked five and a half. After Snow White, Walt ordered it on a five-day week. He next cut back twenty per cent of the Snow White profits to his workers, and then, feeling that perhaps even that wasn’t enough, he gave a party for the whole eight hundred of them just to celebrate. He set the studio working hours as eight to five and took out insurance to cover each individual.

Walt gets slightly abashed when he tries to explain his way of being a boss. ” I like our cartoons to be put together like a symphony,” he explains shyly. ” You know, there’s a conductor—I guess I’m it—and then there are the solo violins, and the horn players, and the strings, and a lot of other fellows, and some of them are more stars than others, but every one has to work together, forgetting himself, in order to produce one whole thing which is beautiful.”

With this thought in mind, he doesn’t make contracts with his animators. He wants them to be free to leave if they so desire ; but the result of this freedom, naturally, is that they seldom do. Walt knows every man in the studio intimately. ” You have to cast artists as you do actors,” he explains. ” Some are better at drawing characters and some are best on flowers. Some artists are funny in every line they sketch, where others are solemn. You have to know all about a man to be sure that he is doing the work he loves best.” So well acquainted is Walt with each man’s work that he can tell at a glance just who has done any given sketch.

He hasn’t a time clock in the place. He runs a school for his artists. It is close by the studio and is free to his workers, even though it costs him $100,000 a year. The men can go to it or not, as they like. He has instructors there to teach the apprentices or to help unsnarl problems that may be puzzling the professionals. Any aspiring youngster whose amateur drawing reveals talent can get into the school, and if he develops at all, he is sure of a job at Disney’s.

Besides the school, Walt has a process laboratory, that is, a lab for creating trick movie effects, where employees may, in Walt’s phrase, just fiddle around. ” You have to keep experimenting,” he explains. ” In order to get a character for a cartoon, you have to keep pecking away at it.”

An example of this ” pecking away ” was the discovery that a fawn was due to be born at the San Diego, California, zoo. Walt kept close watch on that vital statistic and on the day of the main event three animators from Disney’s were sitting close by the mother doe, busily sketching away. The birth of that fawn will become, eventually, the birth of Bambi on the screen.

Walt took $70,000 of the Snow White money and put it into a multiplane camera. Animation of figures has to be photographed through many layers of celluloid, one layer to each group of figures, so that if, for example, humans, animals, flowers, and sky are all in one scene, each item has its own celluloid plane to give an illusion of depth. They had a pretty good multiplane camera before Snow White, but they’ve got a better one now. This new one is a whiz for speed—does four feet of photographing an hour.

Having long since outgrown his present studio, Walt is having a new one built. He thinks it will cost him $750,000, but it will probably cost a million. If you figure that if he keeps on spending this way out of a mere two millions, Walt may soon be broke, let it be remarked that such an happening wouldn’t greatly surprise him.

It wouldn’t worry him, either, because then it would become Roy’s problem.

Roy, of course, knows just how negotiable Walt’s talent is. He was able to borrow a million and a half dollars on the preliminary sketches for Snow White, so there doesn’t seem to be any necessity of either of the brothers getting into any nervous frets. Yet everything they possess is still being gambled with.

The most distinctive of the gamblers is The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Stokowski conducted the music for it exactly as he would conduct its score at a regular concert. Walt never said a word about that, and Stokowski in turn never said a word about the animation. Probably Goethe, who wrote the original story of an apprentice who borrowed his master’s hat and could thus bewitch a broom into doing his bidding, is turning over in his grave at the thought of this story being a vehicle for Mickey Mouse, but if he could see the result, I’m sure he would be enchanted. For a more amusing figure than little Mickey when he stands on the top of the world, making the waves splash mountain-high and moving the stars in their courses could be imagined by no man save Walt Disney. And Mickey’s agony when he can’t stop the magic he has begun is a typical Disney nightmare, too.

This animating great music is one of Walt’s fondest dreams.

He isn’t being highbrow about music or trying to grow away from his public. He was as much attracted to The Sorcerer’s Apprentice by its story as by its sound, which is also true of The Flight of the Bumble Bee of Rimski-Korsakov, which he plans to make next. Stokowski will do the score on that one, too. Then, if Walt can find three more likely subjects, he will make them and put the whole out as a special five-reel musical masterpiece-cartoon subject. He wanted to do Debussy’s The Afternoon of a Faun, but Will Hays wouldn’t let him. Hays said that was too naughty. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice cost around $200,000 to make, for all its one-reel length, and the others will probably be similarly costly, so you see the risk involved, since nothing like them has ever before been created.

Ferdinand the Bull, from the gay book by Munro Leaf, is just a sort of Disney sport. Unless Ferdinand clicks very heavily, he probably will appear only once. I fancy Walt made this one just for the sheer fun of it.

But these things are mere side issues along against Bambi, which is his real work now. (His great loves, in case you want to know, are his work and a very delightful wife and two handsome children.) When Walt started drawing cartoons, the only emotion he knew how to create in them was laughter. Later he learned how to make audiences shiver with fear. When he watched the showings of Snow White, he realized with a thrill that he had discovered how to produce another emotion. He could make people cry.

Only he knows what emotion he will stir with Bambi, but of this you may be reasonably sure : No matter how else he moves us, Bambi will leave the world a gayer and more tolerant place than it was before.

You can tell by the skunk. For a man who can make you feel sorry for a skunk can do anything.

THE END