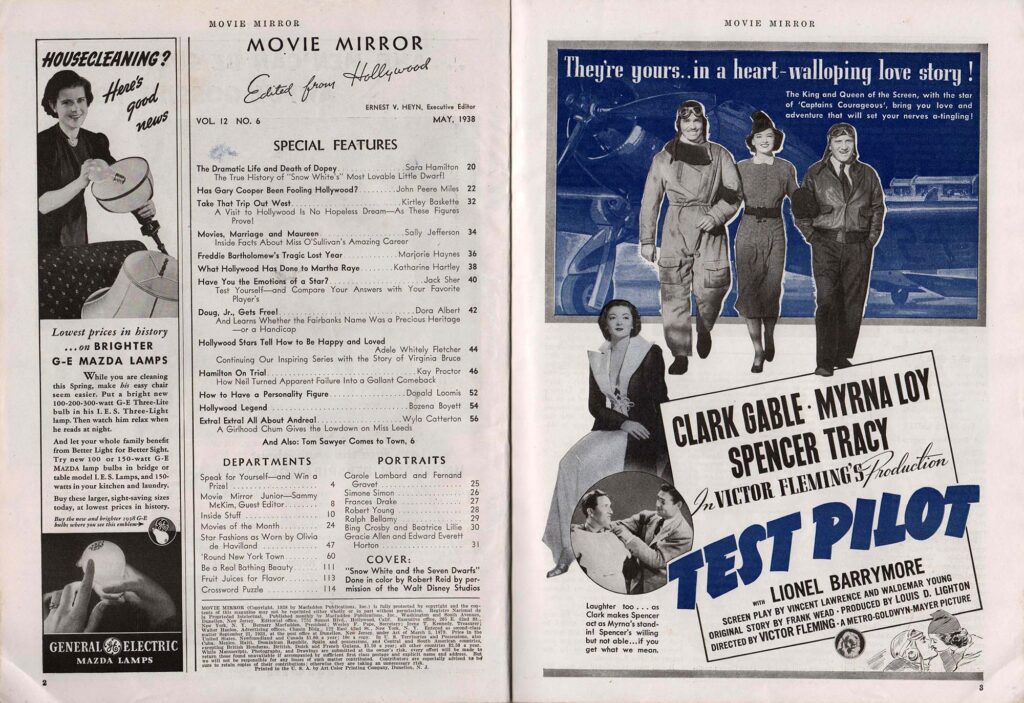

At a time when the film’s success was no longer a secret, magazines were snapping up Snow White visuals for their covers. In its May 1938 issue, Movie Mirror published a front-page image that has since been reproduced on magnets and postcards.

The article, with its “shocking” title (“The Dramatic Life and Death of Dopey”), was intended as a statement by Walt Disney that he would not use the character in any more cartoons, despite his popularity, because he wanted Snow White to remain a special production. Perhaps he learned from Three Little Pigs, where sequels with the same characters were not as resounding a success as the original. Nevertheless, Dopey and his friends would return to the screen several times, notably in the short films Seven Wise Dwarfs and The Winged Scourge.

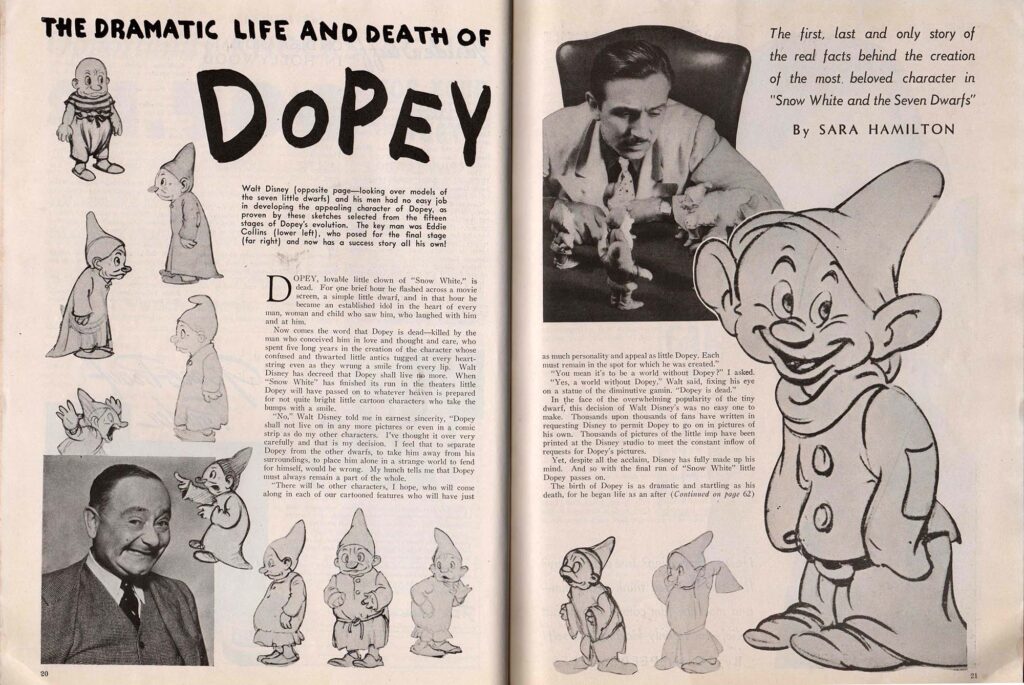

We also get information on the model for the famous dwarf, Eddie Collins, proving that, despite a certain desire not to draw too much light on the actors behind his characters (by omitting them from the credits, for example), Walt Disney wasn’t keeping a total secret on the subject.

The Dramatic Life and Death of Dopey

The first, last and only story of the real facts behind the creation of the most. beloved character in “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” by Sara Hamilton.

Walt Disney (opposite page—looking over models of the seven little dwarfs) and his men had no easy job in developing the appealing character of Dopey, as proven by these sketches selected from the fifteen stages of Dopey’s evolution. The key man was Eddie Collins (lower left), who posed for the final stage (far right) and now has a success story all his own!

DOPEY, lovable little clown of “Snow White,” is dead. For one brief hour he flashed across a movie screen, a simple little dwarf, and in that hour he became an established idol in the heart of every man, woman and child who saw him, who laughed with him and at him.

Now comes the word that Dopey is dead—killed by the man who conceived him in love and thought and care, who spent five long years in the creation of the character whose confused and thwarted little antics tugged at every heart-string even as they wrung a smile from every lip. Walt Disney has decreed that Dopey shall live no more. When “Snow White” has finished its run in the theaters little Dopey will have passed on to whatever heaven is prepared for not quite bright little cartoon characters who take the bumps with a smile.

“No,” Walt Disney told me in earnest sincerity, “Dopey shall not live on in any more pictures or even in a comic strip as do my other characters. I’ve thought it over very carefully and that is my decision. I feel that to separate Dopey from the other dwarfs, to take him away from his surroundings, to place him alone in a strange world to fend for himself, would be wrong. My hunch tells me that Dopey must always remain a part of the whole.

“There will be other characters, I hope, who will come along in each of our cartooned features who will have just as much personality and appeal as little Dopey. Each must remain in the spot for which he was created.”

“You mean it’s to be a world without Dopey?” I asked.

“Yes, a world without Dopey,” Walt said, fixing his eye on a statue of the diminutive gamin. “Dopey is dead.”

In the face of the overwhelming popularity of the tiny dwarf, this decision of Walt Disney’s was no easy one to make. Thousands upon thousands of fans have written in requesting Disney to permit Dopey to go on in pictures of his own. Thousands of pictures of the little imp have been printed at the Disney studio to meet the constant inflow of requests for Dopey’s pictures.

Yet, despite all the acclaim, Disney has fully made up his mind. And so with the final run of “Snow White” little Dopey passes on.

The birth of Dopey is as dramatic and startling as his death, for he began life as an afterthought. It had been decided by Walt and his associates that each of the dwarfs should represent a type known in every community; every-day people who lived and thought as other men. The busy go-getter, therefore, lives on in Doc. The easy-come, easy-go guy exists in Happy. The hay-fever-but-sorry-about-it individual lives in Sneezy, the drowsy-but-not-so-dumb type carries on in Sleepy. The constant grouch is typified in Grumpy.

“What about a goofy kind of guy?” Walt asked, one day after the problem of the seventh dwarf had worn everyone thin. “There’s always a well-meaning, cheerful little goof in every town. Why not a Dopey?”

And so it came to be. Only Dopey, of all the dwarfs, proved to be the problem child. Somewhere in the minds of Disney and his animators the little creature begged to be brought into focus. “Here’s me, here’s me” he seemed to cry pleadingly, but still Walt and his men couldn’t quite get to him.

First, they drew him round and bald and stupid. His clothes fitted his plump body snugly and his wide apart eyes stared helplessly.

It’s not Dopey,” Walt or Dave or Dick would say, flinging aside the drawing. “It’s just not Dopey.”

Finally, the situation was up to eight animators whose sole task was that of bringing forth a Dopey.

Days became heavy with disappointment as pencils flew aimlessly over cartoon drawings. Dopey was draped in close fitting garments, then in clothes ten sizes too big. His cap fell over – his too small ears, lending a grotesque but non-appealing air to the little man.

Nights became hours of feverish unrest as the eight men sat in their respective living rooms staring sullenly, only to rise and pace the floor, back and forth.

“Now,” taunted the wife of one of them, “you know what it feels like to have a child. Only you’ve been in helpless labor almost a year. Little Dopey had better arrive soon or eight papas are going to be very, very sick mothers.”

Months passed. The artists widened Dopey’s mouth. They put him on a reducing diet. They changed his clothes. Still, it just wasn’t Dopey.

“I’m going to forget it all,” one of them finally stormed. “I’m off for a burlesque show.”

Bored, but seeking relaxation, the artist watched a group of half-naked blondes parade in plumpish unison. A strip tease dancer removed a sleazy silk frock with a smirk and a grimace. The artist sat on, wondering why all strip teasers should smirk and grimace.

Suddenly he sat up. Electrified. An odd, plumpish, appealing little man was standing before him. On the stage. Saying something. Something about a girl’s knees. But what did it matter what he said? For there, down there on a Main Street burlesque stage stood—Dopey.

The artist drove home like a man afire. “I saw him,” he cried, wakening his wife. “I saw him! Standing there. His face— sweet, homely, appealing. Our Dopey. Who was it, honey, that said something about God working in a mysterious way His wonders to perform?”

Sleep was out of the question. The artist and his wife ate cheese and crackers and drank root beer until dawn. At eight o’clock the artist was in Walt’s office with the story.

Next night Eddie Collins, tiny, rotund burlesque comedian, lay on his cot in his dressing room resting after his fourth show that day; waiting for his fifth and final performance.

Four men climbed the rickety stairs to his room. “Sorry to intrude, Mr. Collins,” one man spoke, “but my name is Disney.”

The comedian rose and stared. “You mean the man who owns Mickey Mouse?”

Walt laughed and in a whispered aside murmured, “It’s Dopey, all right.”

That night, there in that dressing room, arrangements were made for Eddie Collins to appear twice each month to pose for Dopey. A sum of fifty dollars for three hours’ work every two weeks was agreed upon. At his first appearance Mr. Collins was requested to walk across the stage, greet a young lady and engage in conversation. Not a soul but Collins appeared in the scene. He pantomimed as cameras turned. Then in the Disney sweat box, as the small projection room is called, the reel was run over and over again while animators watched and studied.

Two weeks later at Disney’s studio, Mr. Collins engaged in a pillow fight from which he managed to garner one sole feather upon which to lay his grateful head. Again cameras turned.

For one year the burlesque comedian posed and capered for a Disney camera until finally, in all his beautiful simplicity, Dopey emerged. His eyes had narrowed, his ears had grown larger, his mouth had become elfin; his clothes–still too-large cast-offs from the other dwarfs and slightly bilious in color—covered a babyish little body.

With his complete emerging came character. Life to Dopey was a lark—but one he couldn’t quite understand. Others knew about all the weighty and intricate business of life and the living of it, but no one enjoyed it more than little Dopey, who so willingly, so gladly trudged far behind in the parade of life—happy just to be there—six paces in the rear.

Childish and prankish, too, grew Dopey; placing twin diamonds in his eyes to tease Doc. Gladly, oh ever so willingly, he allowed himself to be trampled, bullied. badgered, ignored—for life was a game and they were allowing Dopey to play. To be with them.

He asked for no gallery or even balcony seat at any great moment of suspense. All he ever expected or took was a lowly place beneath the beard of his friend, there to peer at the wonders going on around him.

In trouble he suffered alone. With a soap cake in his interior, he agonizingly endured in silence, blowing his own bubbles of indigestion, asking and expecting no sympathy. Fearful and yet gamely in the fright scene he climbed those awful stairs alone to meet whatever dreadful fate lay ahead because these, his friends, were asking him to—trusting him—letting him be just one of them.

At first Dopey talked even as the others. They tried out the voice of Doc on Dopey. It didn’t suit. They tried high voices, low voices, shrill voices, deep voices. Nothing suited. “He shall be voiceless, then,” Walt decreed. And it was so.

As sympathy for Dopey seeped into the cartoonists’ hearts, it seeped into the hearts of the creatures that grew on their drawing boards. Snow White and the dwarfs, the deer, the rabbit and even the chicadees, maintained a friendly, protective tolerance for the little member who was not too bright within.

Something of the simplicity of the man Disney crept into the soul of Dopey Disney as meetings between Walt and his men Went on daily.

A typed record of one of those meetings reveals the easy, natural informality between Walt and his men with none of the I’m-a-genius attitude about it.

“Walt,” one of the men begins, according to the record, “I think we should have Dopey very simply presented in this bedtime sequence.”

“No, Dave, I don’t agree,” Walt answers. “I think it would be better if Dopey should have a dream like a puppy. Whimpering and crying. What do you think of that idea, Dick?”

And on and on the quiet conversation runs, with the guiding hand of Walt Disney bringing into full bloom the quaint personality of one Dopey Dwarf.

By sheerest accident they discovered that funny little Susy Q time step used by Dopey at all times. One of the animators had evidently caught the step from a bit of Collins’ pantomiming and used it in a single scene. When the sequence was shown in the projection room, just two months before the picture was released, Walt leaped to his feet. “There it is, boys,” he said, “the final touch to Dopey. With that step he is completed. Dopey has finally arrived.” And so, back they went over four years’ work on Dopey, and drew in the funny little step that brings a laugh from everyone.

Six months before the picture was pronounced finished, a rough cut was shown the wives and families of studio employees. From that moment on Dopey became the special ward of every wife, sister or mother of a Disney worker.

“How’s Dopey?” wives would greet husbands in the evening. “Bless his heart. How you can let that innocent lamb be ignored that way is beyond me.”

Accusing looks were cast over many a pot roast as a wife scolded.

“Little lamb. He’s just a baby, that’s all. Some people have no heart, treating that darling Dopey like a step-child.”

The girls who inked in the pictures fought for the privilege of inking in Dopey. Even hardboiled studio artists, used to every conceivable type of character, broke down in a body and openly and shamelessly admitted their fondness for Dopey.

“It’s the eternal optimism of him,” one worker said, “brushing off that ridiculous mouth for a kiss from Snow White that always lit on his head instead. I fought for Dopey to get just one kiss on those pursed lips before she left him. He was such a well-meaning, harmless little fellow, it wouldn’t have hurt any.”

Unconsciously, perhaps, they injected a bit of the Irish elf in Dopey. A bit that seeped through the work of Eddie Collins whose parents on both sides were born in old Erin. A land where pixies still roam the meadowlands by night and tiny elves peep out from cabbage leaves for all the world like Dopey beneath the beard of a brother dwarf.

The same blue eyes of Mr. Collins mirror the happy soul of little Dopey—the only dwarf whose eyes aren’t brown. In fact, there was so much of Eddie in Dopey, Walt felt that the comedian should continue on the screen. When his posings at the Disney studio were completed, Walt wrote a letter to Lew Schreiber, casting director for 20th Century-Fox, who immediately signed the actor. A bit in “In Old Chicago” grew into a fat role in “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” and Mr. Collins found his world of burlesque left behind—thanks to Dopey.

A jolly, kindly family man whose wife fretted and worried over her devoted husband, lest he take cold in draughty dressing rooms or lest he overwork, Eddie is proud that he never uttered an obscene word on a stage—not even a Main Street burlesque one.

For years Eddie and his wife toured the country with his own troupe, until the Los Angeles job gave him the realization of a great dream—a little chicken ranch in the country.

Yeah, Dopey is my best friend,” Eddie told me. “I can’t tell you how I feel about him. I don’t like to think somehow, that he isn’t always going on and on where we can be together again.”

“We always knew, my wife and the kids and I, that something or someone would lift me out of that work and now look, it had to be Dopey. God bless his little heart, says I. And says my family.”

And now, as dramatically as Dopey came to life, he leaves.

But not to be forgotten. Forever he’ll live in the hearts of all who have seen him. And who knows but years from now we may be flocking back, again and again. to behold the wonders of Snow White and the seven little dwarfs, to chuckle with glee and even shed a tear for the little tyke on the end—out of step—out of time—but happy.

Just little Dopey, marching on.