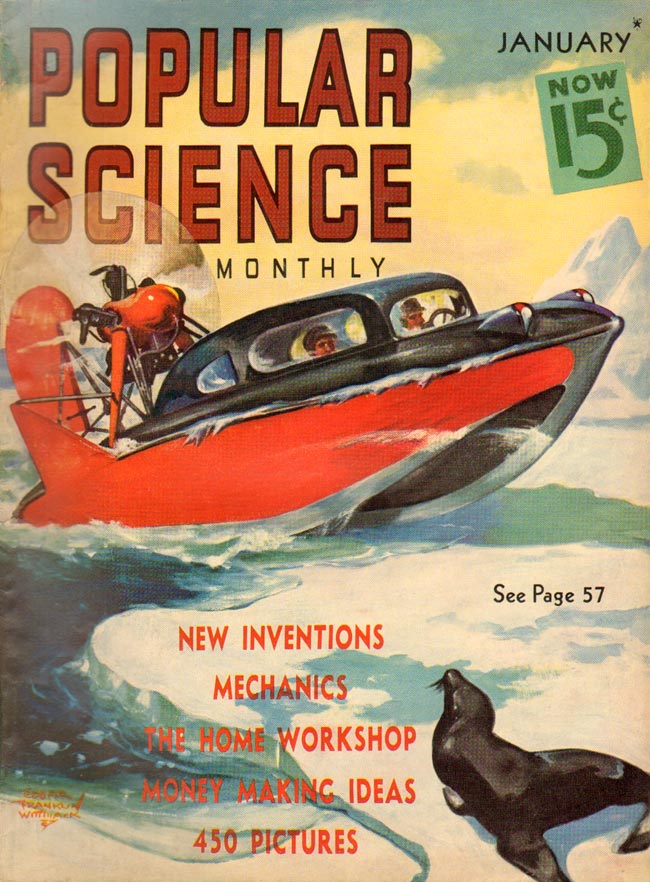

This magazine, published in January 1938 (Volume 132, Number 1), explains in great detail with several pictures how to make a full length cartoon in the article “Putting a Fairy Tale on the Screen” by Andrew R. Boone on page 50.

The magazine sold for 15 cents and was edited by Raymond J. Brown.

Putting a Fairy Tale on the Screen

A Famous Fairy Tale Is Brought to the Screen as the Pioneer Feature-Length Cartoon in Color

By Andrew R. Boone

Behind the black walls of an air-conditioned Hollywood studio laboratory, the shutter on a strange eight-deck camera flicked open and shut the other day, exposing the last of 362,919 frames of color film. At that instant was completed the first feature-length motion-picture cartoon ever created, one requiring more than 1,500,000 individual pen-and-ink drawings and water-color paintings. Also, at that moment, depth, a sense of perspective and distance hitherto seen only in “live action” pictures, sprang into being for cartoons.

Both the giant camera and the picture had their beginnings in a decision made four years ago by Walt Disney, famed creator of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, to produce a feature based on a well-known folk tale. “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” a movie version of Grimm’s famous fairy tale filmed by the multiplane camera, is the result.

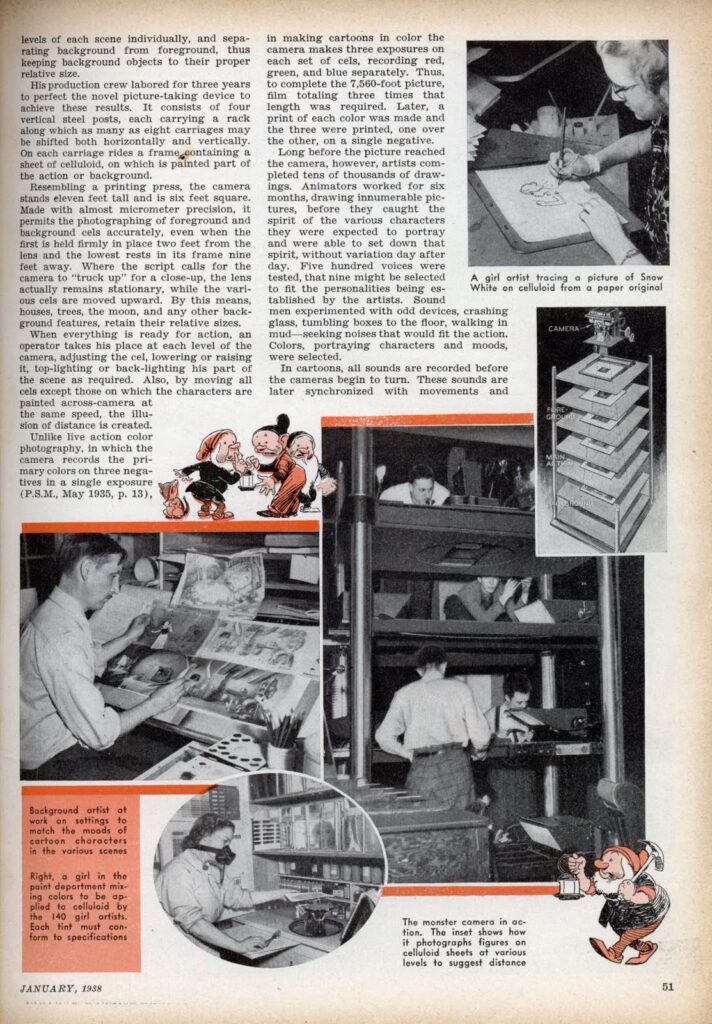

Heretofore, movie cartoons have been series of photographs of drawings and paintings on oblong pieces of celluloid held in a single plane. That is, when photographed the “cels,” or transparent sheets bearing the drawings, were stacked like pieces of paper. On each was painted a part of the scene reaching the screen.

Disney wanted to increase the eye value of the many paintings making up a picture by achieving a soft-focus effect on the backgrounds, illuminating the various levels of each scene individually, and separating background from foreground, thus keeping background objects to their proper relative size.

His production crew labored for three years to perfect the novel picture-taking device to achieve these results. It consists of four vertical steel posts, each carrying a rack along which as many as eight carriages may be shifted both horizontally and vertically. On each carriage rides a frame containing a sheet of celluloid, on which is painted part of the action or background.

Resembling a printing press, the camera stands eleven feet tall and is six feet square. Made with almost micrometer precision, it permits the photographing of foreground and background cels accurately, even when the first is held firmly in place two feet from the lens and the lowest rests in its frame nine feet away. Where the script calls for the camera to “truck up” for a close-up, the lens actually remains stationary, while the various cels are moved upward. By this means, houses, trees, the moon, and any other background features, retain their relative sizes.

When everything is ready for action, an operator takes his place at each level of the camera, adjusting the cel, lowering or raising it, top-lighting or back-lighting his part of the scene as required. Also, by moving all cels except those on which the characters are painted across-camera at the same speed, the illusion of distance is created.

Unlike live action color photography, in which the camera records the primary colors on three negatives in a single exposure (P.S.M., May 1935, p. 13), in making cartoons in color the camera makes three exposures on each set of cels, recording red, green, and blue separately. Thus, to complete the 7,560-foot picture, film totaling three times that length was required. Later, a print of each color was made and the three were printed, one over the other, on a single negative.

Long before the picture reached the camera, however, artists completed tens of thousands of drawings. Animators worked for six months, drawing innumerable pictures, before they caught the spirit of the various characters they were expected to portray and were able to set down that spirit, without variation day after day. Five hundred voices were tested, that nine might be selected to fit the personalities being established by the artists. Sound men experimented with odd devices, crashing glass, tumbling boxes to the floor, walking in mud—seeking noises that would fit the action. Colors, portraying characters and moods, were selected.

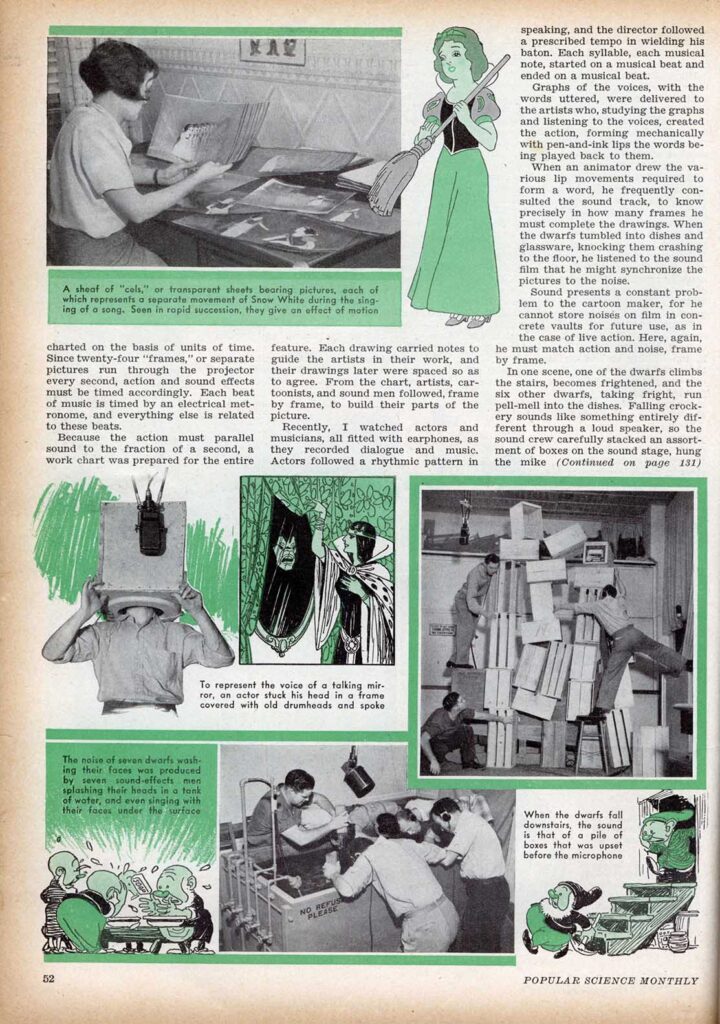

In cartoons, all sounds are recorded before the cameras begin to turn. These sounds are later synchronized with movements and charted on the basis of units of time. Since twenty-four “frames,” or separate pictures run through the projector every second, action and sound effects must be timed accordingly. Each beat of music is timed by an electrical metronome, and everything else is related to these beats.

Because the action must parallel sound to the fraction of a second, a work chart was prepared for the entire feature. Each drawing carried notes to guide the artists in their work, and their drawings later were spaced so as to agree. From the chart, artists, cartoonists, and sound men followed, frame by frame, to build their parts of the picture.

Recently, I watched actors and musicians, all fitted with earphones, as they recorded dialogue and music. Actors followed a rhythmic pattern in speaking, and the director followed a prescribed tempo in wielding his baton. Each syllable, each musical note, started on a musical beat and ended on a musical beat.

Graphs of the voices, with the words uttered, were delivered to the artists who, studying the graphs and listening to the voices, created the action, forming mechanically with pen-and-ink lips the words being played back to them.

When an animator drew the various lip movements required to form a word, he frequently consulted the sound track, to know precisely in how many frames he must complete the drawings. When the dwarfs tumbled into dishes and glassware, knocking them crashing to the floor, he listened to the sound film that he might synchronize the pictures to the noise.

Sound presents a constant problem to the cartoon maker, for he cannot store noises on film in concrete vaults for future use, as in the case of live action. Here, again, he must match action and noise, frame by frame.

In one scene, one of the dwarfs climbs the stairs, becomes frightened, and the six other dwarfs, taking fright, run pell-mell into the dishes. Falling crockery sounds like something entirely different through a loud speaker, so the sound crew carefully stacked an assortment of boxes on the sound stage, hung the mike near-by, and recorded the series of bumps. and crashes as they tumbled to the floor. Later, artists, listening to a play-back of the sound track, matched it bump by bump, the pictures being drawn to synchronize with the noises. Breaking glass later was matched when two men dropped a large pane eight feet from a ladder to the floor.

Other actions called for in the script complicated the sound men’s job. How would a talking mirror sound? What kind of noise would seven dwarfs make when eating soup—and, more important, how could the noise be represented on the sound track? Posers, these problems; but ingenious magicians with sound solved them.

It was decided that should a mirror ever actually speak, there would emerge from its silvered surface a sepulchral, masculine voice. For weeks, voices were recorded in boxes, through sheets, before sounding boards. At last a sound technician hit upon the idea of building a square box with old drumheads stretched taut over five sides, leaving an opening in the sixth. Through that opening an actor placed his head, spoke the prescribed lines into a nearby mike, and became the talking mirror.

As for the soup, seven studio workers sat at a table for a day and a half, intermittently sipping malted milk and eating wafers. Short, quick “slurps” represented tenor parts; long “slurps,” bass.

When the dwarfs washed their faces and sang, seven men skilled in the recording of unusual sounds stood around a water tank the size of five bath tubs, alternating washing their faces and dipping their heads into the water, singing at times while their faces were submerged. The underwater sounds being recorded by a shielded microphone. And to represent a character slushing through a fanciful swamp, the tank was filled with mud, and a man walked in the mud several hours, in tempo with a metronome whose tick-tick came to him through earphones.

Meanwhile, application of color, which has achieved great perfection in cartoons, has become as mechanical as the creation of sound effects. For a full-figure shot, Snow White appears in fifteen tints, selected from among 350 standard colors available in the studio paint shop. These vary from tint 685 1/2 (yellow shoes) to pastel 23 ( cheeks). When she sings, six colors are added to her eyes and mouth for close-ups, these ranging from orange-yellow on the lids to light red for the lips. Upon each drawing is noted the particular colors to be added to the several areas, and thereafter scores of girls complete the many paintings by spotting colors according to number.

Paintings on three to seven cels appear in a single shot, the number depending upon the action and characters. In its simplest form; usually four cels are used.

Suppose Snow White is photographed singing. For this sequence, provided her figure is to move, the lowest cel contains the “setting,” perhaps a wall of the house. Next above appears her body, minus arms and head.

To show the necessary movements, which match the song recorded several weeks earlier, two cels, one containing a painting of her head and the other her arms, are placed in series above her body. After each exposure, new cels are put in to take the place of these.

This process continues for perhaps sixty frames, enough to complete a well-rounded word. Projected at standard speed of twenty-four pictures a second, the many paintings blend to create the necessary illusion of motion in color.

Once past the animation stage, which consists of completing the multitude of drawings representing whole and part figures, making the cartoon was largely mechanical, although requiring a precision found in the finest machine manufacture.

“Ink and paint” represent the manufacturing bottle neck, for a movie cartoon can progress no more rapidly than skilled hands complete the multitude of drawings. Since this cartoon required an average of twenty-two individual painted cels for each foot of completed picture, 166,352 finished paintings were exposed to the camera.

These moved at the rate of ninety feet of film daily through the camera, which, requiring 1,960 paintings every twenty-four hours, represent the world’s biggest and most exacting job of painting.