Film Pictorial is a British magazine that covered the original release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in several issues. In 1939, Film Pictorial was absorbed by Picture Show magazine.

February 26, 1938

The article in that issue mentions the censorship issues that plagued the film in Great Britain, poking fun at the censors. Here is the text:

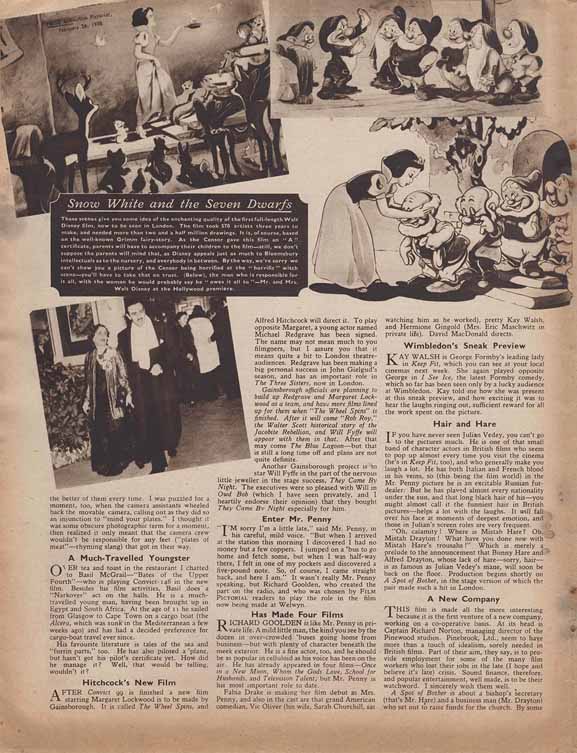

These scenes give you some idea of the enchanting quality of the first full-length Walt Disney film, now to be seen in London. The film took 570 artists three years to make, and needed more than two and a half million drawings. It is, of course, based on the well-known Grimm fairy-story. As the Censor gave the film an “A” certificate, parents will have to accompany their children to the film – still, we don’t suppose the parents will mind that, as Disney appeals just as much to Bloomsbury intellectuals as to the nursery, and everybody in between. By the way, we’re sorry we can’t show you a picture of the Censor being horrified at the “horrific” witch scene – you’ll have to take that on trust. (Below), the man who is responsible for it all, with the woman he would probably says he “owes it all to” – Mr. and Mrs. Walt Disney at the Hollywood premiere.

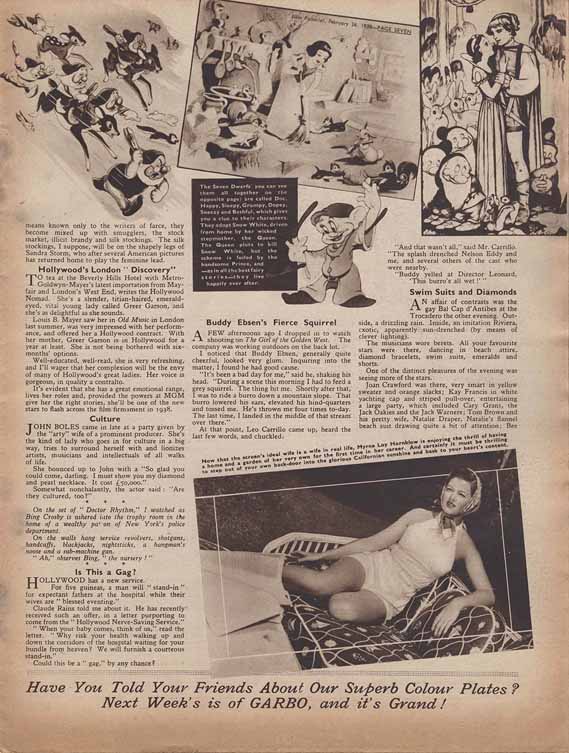

The Seven Dwarfs (you can see them all on the opposite page) are called Doc, Grumpy, Dopey, Sneezy and Bashful, which gives you a clue to their characters. They adopt Snow White, driven from home by her wicked stepmother, the Queen. The Queen plots to kill Snow White, but the scheme is foiled by the handsome Prince, and – as in all the best fairy stories – they live happily ever after.

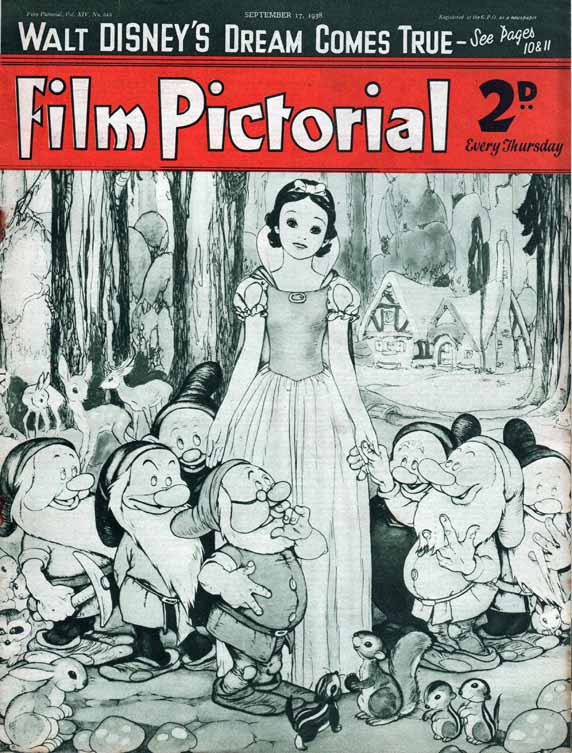

September 17, 1938

Page ten and eleven, an article about Snow White with pictures of the cast and of the characters. We’re talking here about the genesis of the film, not its production. The author even recalls Walt Disney’s visit to Europe a few years before, and raises the possibility of making Alice in Wonderland in the future. Weaknesses in the animation of the human characters are mentioned. Underneath the actors’ photos are the reasons for their popularity, as explained to Britons unfamiliar with American radio and stage stars. Here is the text:

Walt Disney Makes His Dream Come True

As a boy, Disney was fascinated by the story of “Snow White”. He dreamed of bringing “Snow White” to the screen. He passed on his great idea to others, only to be told that such a dream could never become successful reality. But, as R. Ewart Williams tells you here, Disney refused to be discouraged.

After a private showing of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, members of the audience formed little groups to discuss the film. And everywhere one heard the same remark: “Is it going to revolutionize film? Does it mean that actors will no longer be necessary?”

To my mind, that is fantastic point of view. It is rather like saying that labour-saving devices in the home mean the end of the housewife. But as I listened, my mind went back nearly three years to the day when Walt Disney arrived in London for a holiday. A big crowd was at the station to greet him, and later in the day a party was held in his honour. And many of the people who attended the private showing of Snow White were guest at that party. Disney was surrounded by a crowd who asked him many questions, and told him how they would make his cartoon films if they were in his shoes. The genius who had created Mickey Mouse and the Silly Symphonies listened politely. Then he outlined his plans for Snow White, admitting that he was feeling nervous about the possibility of its success.

Glad I was wrong

His audience listened with appropriate enthusiasm, but when he had gone they declared he was mad to attempt a full-length cartoon film. I know – because I was one of them. I did not believe it was possible for a cartoon to hold an audience’s attention for an hour and 30 minutes. Having seen Snow White I am glad I was wrong.

Once again Disney has shown that he is the logical successor to Hans Andersen and the Grimm Brothers. He alone is creating worthy fairy stories which delight children by their cleverness, and adults by their artistry.

One of the more intelligent newspaper critics has described Snow White as the most important event in the cinema since the advent of talking films. He lists is also with Birth of a Nation, a film which changed the entire technique of film-making.

Yet I doubt if Disney deliberately intended to make this effort. In creating Snow White, his main desire was to prove that a full-length cartoon film was capable of maintaining interest. He also wanted to fulfil a childhood dream.

As a boy, the Grimms’ story of Snow White fascinated him; and when it was produced a s a play, he saved his pennies so that he could see it. And he hoped that one day he would be able to act in it. Instead of becoming an actor, Disney chose cartoon work. And after many years of struggle, the success of Mickey Mouse and the Silly Symphonies gave him the opportunity of creating his own interpretation of his favourite fairy story.

It was the success of Three Little Pigs that convinced him the time was ripe to put his big idea into practice. Casually, in general conversation, he passed the idea on to his staff. Most of them were afraid of it. They, too, felt that no cartoon film, without a single human character, could sustain interest for over an hour.

Four Years to Complete

Disney had his way, and you probably know the story of how the film was made. Thousands of preliminary sketches – backgrounds, character models and stage setting – were drawn. The story was written and re-written. Dialogue was written and discarded. Living models had to be found to pose for the artists, voice doubles had to be instructed and tested.

By the process of trial and error, the film was gradually created. It took nearly four years to complete, and £250,000 was spent. If the experiment had failed, it might have meant a serious set-back to Disney’s triumphant career. It has not failed, although Disney has been quoted as saying that he is not satisfied with the results. He considers the human beings to be badly drawn, and says that they behave like puppets. He is quite right, of course. It is only natural for a creative artist to feel that he has fallen short of his objective; but it is the dwarfs and animals that give the film its charm. Here he is on ground that he has already charted thoroughly, whereas he is not yet certain how to treat his human beings.

But these weaknesses, which have been seized upon and elaborated by would-be highbrows, are really unimportant. The significance of Snow White is that it has brought something new to the cinema at a time when it was badly needed. Its success makes fantasy possible on the screen.

It is not the first time that fantasy has been attempted. Other film producers have tried, using real actors to play the characters. There have, for example, been two version of Alice in Wonderland, and each failed because actors were incapable of playing such parts as the March Hare and the Cheshire Cat.

As Disney himself has said, “There are many reasons why the future of the full-length animated picture is practically boundless. It has so few of the limitations surrounding other types of cinema entertainment. We can do so much with colour. Not only birds and animals, but also inanimate objects can behave just as we wish them to behave.”

It is because he is freed from cinematic conventions that I hope Disney will one day attempt the childhood classic, Alice in Wonderland. He should do so, if only to correct the bad impression of Hollywood’s two previous efforts. Cannot you pictures his interpretation of the March Hare, the Cheshire Cat, and the White Rabbit “with a pair of white kid gloves in one hand and a large fan in the other”?

Any lover of pantomimes and fantasies could easily make a score of suggestions, but perhaps it would be better to leave it to Disney himself. He has his own ideas for exploring the new cinematic fields that he has opened, and is already well advanced with his second feature, Adventures of Pinocchio. Let us be satisfied that he has enriched the screen by his genius, and trust him to maintain the high standard that he has set with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

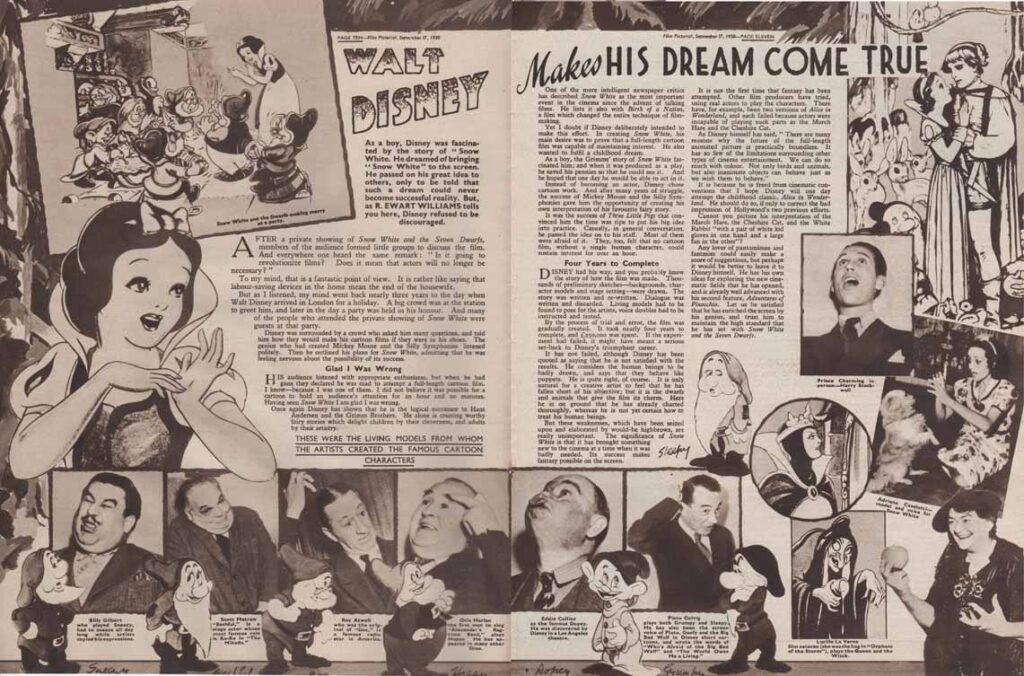

These were the living models from whom the artists created the famous cartoon characters.

- Billy Gilbert who played Sneezy, had to sneeze all day long while artists copied his expressions.

- Scott Mattraw “Bashful” is a stage actor whose most famous role is Ko-Ko in “The Mikado”.

- Roy Atwell who was the original of “Doc” is a famous radio star in America.

- Otis Harlan the first man to sing “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” plays Happy. He has appeared in many other films.

- Eddie Collins as the famous Dopey. He was discovered by Disney in a Los Angeles theater.

- Pinto Colvig plays both Grumpy and Sleepy. He has also been the screen voices of Pluto, Goofy and the Big Bad Wolf in Disney short cartoons, and wrote the words of “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf” and “The World Owes Me a Living”.

- Lucille La Verne film veteran (she was the hag in “Orphans of the Storm”), plays the Queen and the Witch.

- Adriana Caselotti – model and voice for Snow White.

- Prince Charming in person – Harry Stockwell.