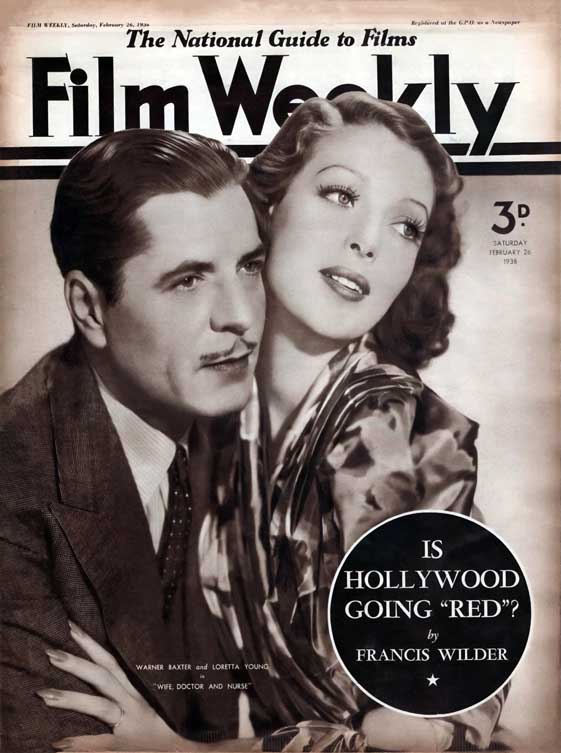

Film Weekly is a British film magazine launched in 1928, edited by Herbert Thompson. In 1939, it merged with Picturegoer.

February 26, 1938

In this issue of the magazine, there are no less than three articles in relation with the initial release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in London: “Walt Disney, Pioneer, probably written by editor Herbert Thompson, “Genius with a pencil” by Lionel Clynton, and the film’s critic in the section “Looking at the week’s news films”.

Walt Disney, Pioneer

by Unknown journalist (February 26, 1938)

ONLY vision, courage and experiment have made the cinema live and can keep it alive.

One of the boldest and most active pioneers in the present-day cinema is Walt Disney, cartoonist. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was his most risky experiment.

Everybody told him that a feature-length cartoon would be no good. Even his loyal staff were scared by his fantastic proposal.

But Disney went ahead. He spent three years putting his idea into practice. 570 artists were employed to make two and a half million pastel drawings.

Counting £50,000 spent on technical experiment, Disney risked £240,000 on an ideal only he believed in.

★

ALREADY Snow White’s five-weeks’ run at the Radio City Music Hall in New York, has brought in £120,000, half the cost of Disney’s great gamble.

It not only broke the previous record of a three-weeks’ run at the world’s biggest cinema.

It exceeded the normal box-office receipts for every day of its run.

We are proud that filmgoers have so substantially rewarded Disney’s daring. For courage in experiment is the most valuable and vital commodity in films.

★

NOW Snow White has reached London. We see for ourselves that Disney has proved his point, that there is a future for the feature-length cartoon.

Now he can go forward to new and even more imaginative experiments in the same field. There remains the question of horror.

Some of the horrific moments are among the best scenes. Whether they are suitable for children is highly debatable.

We believe that in future Disney must decide whether he is making films for the adult world or for the entertainment of children.

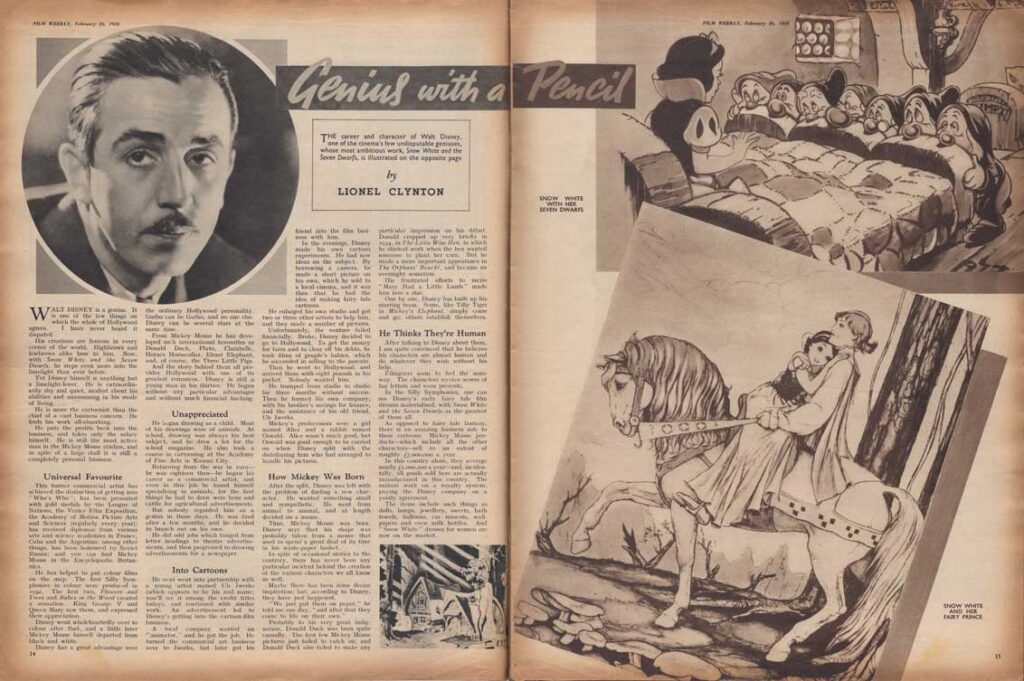

Genius with a Pencil

by Lionel Clynton (February 26, 1938)

The career and character of Walt Disney, one of the cinema’s few undisputable geniuses, whose most ambitious work, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, is illustrated on the opposite page.

WALT DISNEY is a genius. It is one of the few things on which the whole of Hollywood agrees. I have never heard it disputed.

His creations are famous in every corner of the world. Highbrows and lowbrows alike bow to him. Now, with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, he steps even more into the limelight than ever before.

Yet Disney himself is anything but a limelight-lover. He is extraordinarily shy and quiet, modest about his abilities and unassuming in his mode of living.

He is more the cartoonist than the chief of a vast business concern. He finds his work all-absorbing.

He puts the profits back into the business, and takes only the salary himself. He is still the most active man in the Mickey Mouse studios, and in spite of a large staff it is still a completely personal business.

Universal Favourite

This former commercial artist has achieved the distinction of getting into “Who’s Who” ; has been presented with gold medals by the League of Nations, the Venice Film Exposition, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (regularly every year) ; has received diplomas from various arts and science academies in France, Cuba and the Argentina ; among other things, has been honoured by Soviet Russia ; and you can find Mickey Mouse in the Encyclopædia Britannica.

He has helped to put colour films on the map. The first Silly Symphonies in colour were produced in 1932. The first two, Flowers and Trees and Babes in the Woods created a sensation. King George V and Queen Mary saw them, and expressed their appreciation.

Disney went wholeheartedly over to colour after that, and a little later Mickey Mouse himself departed from black and white.

Disney has a great advantage over the ordinary personality. Garbo can be Garbo, and no one else. Disney can be several stars at the same time.

From Mickey Mouse he has developed such international favourites as Donald Duck, Pluto, Clarabelle, Horace Horsecollar, Elmer Elephant, and, of course, the Three Little Pigs.

And the story behind them all provides Hollywood with one of its greatest romances. Disney is still a young man in his thirties. He began without any particular advantages and without much financial backing.

Unappreciated

He began drawing as a child. Most of his drawings were of animals. At school, drawing was always his best subject, and he drew a lot for the school magazine. He also took a course in cartooning at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kansas City.

Returning from the war in 1919 – he was eighteen then – he began his career as a commercial artist, and even in this job he found himself specialising in animals, for the first things he had to draw were hens and cattle for agricultural advertisements.

But nobody regarded him as a genius in those days. He was fired after a few months, and he decided to branch out on his own.

He did odd jobs which ranged from letter headings to theatre advertisements, and then progressed to drawing advertisements for a newspaper.

Into Cartoons

He next went into partnership with a young artist named Ub Iwerks (which appears to be his real name ; you’ll see it among the credit titles today), and continued with similar work. An advertisement led to Disney’s getting into the cartoon-film business.

A local company wanted an “animator” and he got the job. He turned the commercial art business over to Iwerks, but later got his friend into the film business with him.

In the evenings, Disney made his own cartoon experiments. He had new ideas on the subject. By borrowing a camera, he made a short picture on his own, which he sold to a local cinema, and it was then that he had the idea of making fairytale cartoons.

He enlarged his own studio and got two or three other artists to help him, and they made a number of pictures.

Unfortunately, the venture failed financially. Broke, Disney decided to go to Hollywood. To get the money for fares, and to clear off his debts, he took films of people’s babies, which he succeeded in selling to the parents.

Then he went to Hollywood, and arrived there with eight pounds in his pocket. Nobody wanted him.

He tramped from studio to studio for three months without success. Then he formed his own company, with his brother’s savings for finance, and the assistance of his old friend, Ub Iwerks.

Mickey‘s predecessors were a girl named Alice and a rabbit named Oswald. Alice wasn’t much good, but Oswald was good enough to be carried on when Disney split with the distributing firm who had arranged to handle his pictures.

How Mickey was born

After the split, Disney was left with the problem of finding a new character. He wanted something small and sympathetic. He went from animal to animal and at length decided on a mouse.

Thus, Mickey Mouse was born. Disney says that his shape was probably taken from the mouse that used to spend a great deal of its time in his waste-paper basket.

In spite of occasional stories to the contrary, there has never been any particular incident behind the creation of the various characters we all know so well.

Maybe there has been some divine inspiration ; but according to Disney, they have just happened.

“We just put them on paper,” he told me one day, “and after that they come to live on their own,”

Probably to his very great indignation, Donald Duck was born quite casually. The first few Mickey Mouse pictures just failed to catch on ; and Donald Duck also failed to make any particular impression on his debut. Donald cropped up very briefly in 1934 in The Little Wise Hen in which he shirked work when the hen wanted someone to plant her corn. But he made a more important appearance in The Orphan’s Benefit, and became an overnight sensation.

His frustrated efforts to recite “Mary had a little lamb” made him into a star.

One by one Disney has built up his starring team. Some like Tilly Tiger in Mickey’s Elephant, simply come and go ; others established themselves.

He thinks they’re human

After talking to Disney about them, I am quite convinced that he believes his characters are almost human and do whatever they wish without his help.

Filmgoers seem to feel the same way. The characters receive scores of fan letters and even presents.

In the Silly Symphonies, one can see Disney’s early fairy tale film dreams materialised, with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs as the greatest of them all.

As opposed to fairy tale fantasy, there is an amazing business side to these cartoons. Mickey Mouse products – which include all the other characters – sell to an extent of roughly £7,000,000 a year.

In this country alone, they average nearly £2,000,000 a year – and, incidentally, all goods sold here are actually manufactured in this country. The makers work on a royalty system, paying the Disney company on a yearly agreement.

The items include such things as dolls, lamps, jewellery, sweets, bath towels, balloons, car mascots, wallpapers, and even milk bottles. And “Snow White” dresses for women are now on the market.

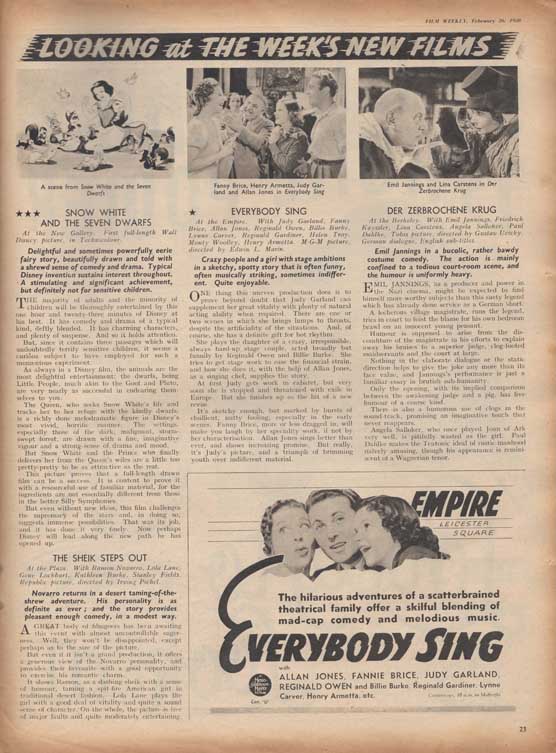

Looking at the week’s new films

by Unknown Journalist (February 26, 1938)

★★★ SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS

At the New Gallery. First full-length Walt Disney picture, in Technicolour.

Delightful and sometimes powerfully eerie fairy story, beautifully drawn and told with a shrewd sense of comedy and drama. Typical Disney invention sustains interest throughout.

A stimulating and significant achievement, but definitely not for sensitive children.

The majority of adults and the minority of children will be thoroughly entertained by this one hour and twenty-three minutes of Disney at his best. It has comedy and drama of a typical kind, deftly blended. It has charming characters, and plenty of suspense. And so it holds attention.

But, since it contains three passages which will undoubtedly terrify sensitive children, it seems a curious subject to have employed for such a momentous experiment.

As always in a Disney film, the animals are the most delightful entertainment; the dwarfs, being Little People, much akin to the Goof and Pluto, are very nearly as successful in endearing themselves to you.

The Queen, who seeks Snow White’s life and tracks her to her refuge with the kindly dwarfs, is a richly done melodramatic figure in Disney’s most vivid, horrific manner. The settings, especially those of the dark, malignant, storm-swept forest, are drawn with a fine, imaginative vigour and a strong sense of drama and mood.

But Snow White and the Prince who finally delivers her from the Queen’s wiles are a little too pretty-pretty to be as attractive as the rest.

This picture proves that a full-length drawn film can be a success. It is content to prove it with a resourceful use of familiar material, for the ingredients are not essentially different from those in the better Silly Symphonies.

But even without new ideas, this film challenges the supremacy of the stars and, in doing so, suggests immense possibilities. That was its job, and it has done it very finely. Now perhaps Disney will lead along the new path he has opened up.