Picturegoer is a British movie magazine that was originally published in 1921, the result of a merger of several magazines that originated in 1911. At the time of the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and since 1931, it was a weekly magazine and remained so until September 1939, when it became bi-weekly. The magazine disappeared after its April 23, 1960 issue.

December 12, 1937

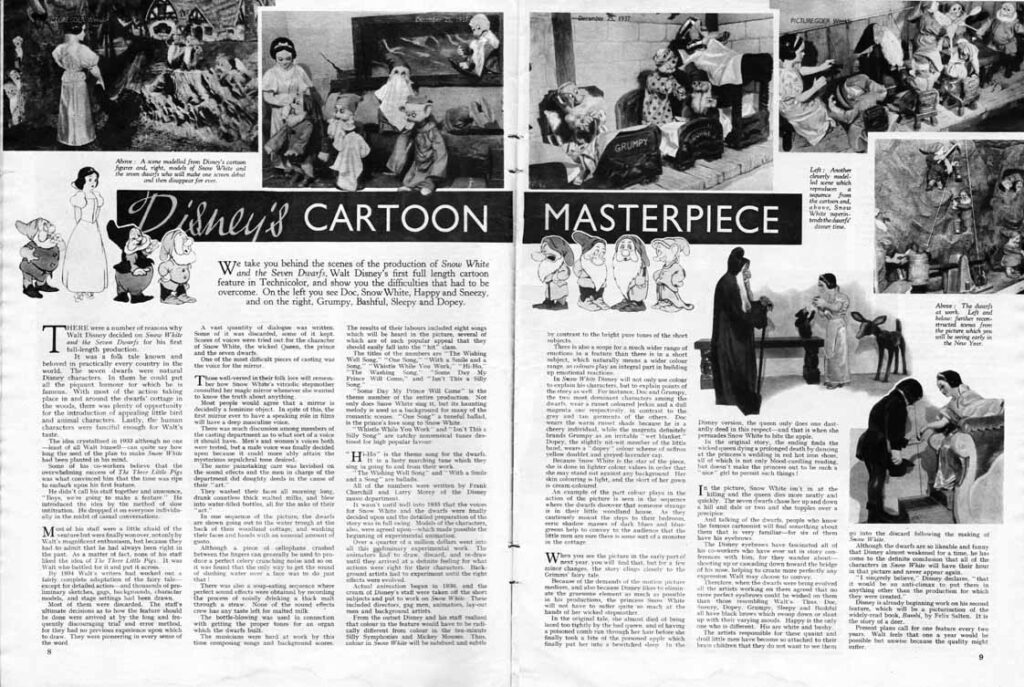

As the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is still to come in the USA, and of course in Great Britain, Picturegoer announces an article revealing the “secrets of Disney’s million-dollar fairy-tale” on page 8 and 9. It is illustrated by pictures of scenes of the film recreated with models. It is not specified where the models come from. Here is the text.

Disney’s Cartoon Masterpiece

We take you behind the scenes of the production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Walt Disney’s first full length cartoon feature in Technicolor, and show you the difficulties that had to be overcome. On the left you see Doc, Snow White, Happy and Sneezy, and on the right, Grumpy, Bashful, Sleepy and Dopey.

There were a number of reasons why Walt Disney decided on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs for his first full-length production.

It was a folk tale known and beloved in practically every country in the world. The seven dwarfs were natural Disney characters. In them he could put all the piquant humour for which he is famous. With most of the action taking place in and around the dwarfs’ cottage in the woods, there was plenty of opportunity for the introduction of appealing little bird and animal characters. Lastly, the human characters were fanciful enough for Walt’s taste.

The idea crystallised in 1933 although no one -least of all Walt himself-can quite say how long the seed of the plan to make Snow White had been planted in his mind.

Some of his co-workers believe that the overwhelming success of The Three Little Pigs was what convinced him that the time was ripe to embark upon his first feature.

He didn’t call his staff together and announce, ” Boys, we’re going to make a feature.” He introduced the idea by the method of slow infiltration. He dropped it on everyone individually in the midst of casual conversations.

Most of his staff were a little afraid of the venture but were finally won over, not only by Walt’s magnificent enthusiasm, but because they had to admit that he had always been right in the past. As a matter of fact, none of his staff liked the idea of The Three Little Pigs. It was Walt who battled for it and put it across.

By 1934 Walt’s writers had worked out a fairly complete adaptation of the fairy tale–except for detailed action-and thousands of preliminary sketches, gags, backgrounds, character models, and stage settings had been drawn.

Most of them were discarded. The staff’s ultimate decisions as to how the feature should be done were arrived at by the long and frequently discouraging trial and error method, for they had no previous experience upon which to draw. They were pioneering in every sense of the word.

A vast quantity of dialogue was written. Some of it was discarded, some of it kept. Scores of voices were tried out for the character of Snow White, the wicked Queen, the prince and the seven dwarfs.

One of the most difficult pieces of casting was the voice for the mirror.

Those well-versed in their folk lore will remember how Snow White’s vitriolic stepmother consulted her magic mirror whenever she wanted to know the truth about anything.

Most people would agree that a mirror is decidedly a feminine object. In spite of this, the first mirror ever to have a speaking role in films will have a deep masculine voice.

There was much discussion among members of the casting department as to what sort of a voice it should have. Men’s and women’s voices both were tested, but a male voice was finally decided upon because it could more ably attain the mysterious sepulchral tone desired.

The same painstaking care was lavished on the sound effects and the men in charge of the department did doughty deeds in the cause of their ” art.”

They washed their faces all morning long, drank countless thick malted milks, and blew into water-filled bottles, all for the sake of their ” art.”

In one sequence of the picture, the dwarfs are shown going out to the water trough at the back of their woodland cottage, and washing their faces and hands with an unusual amount of gusto.

Although a piece of cellophane crushed between the fingers can generally be used to produce a perfect celery crunching noise and so on it was found that the only way to get the sound of slushing water over a face was to do just that !

There was also a soup-eating sequence where perfect sound effects were obtained by recording the process of noisily drinking a thick malt through a straw. None of the sound effects crew has any taste left for malted milk.

The bottle-blowing was used in connection with getting the proper tones for an organ which the dwarfs built.

The musicians were hard at work by this time composing songs and background scores.

The results of their labours included eight songs which will be heard in the picture, several of which are of such popular appeal that they should easily fall into the ” hit” class.

The titles of the numbers are ” The Wishing Well Song,” ” One Song,” ” With a Smile and a Song,” ” Whistle While You Work,” ” Hi-Ho,” ” The Washing Song,” ” Some Day My Prince Will Come,” and ” Isn’t This a Silly Song.”

” Some Day My Prince Will Come” is the theme number of the entire production. Not only does Snow White sing it, but its haunting melody is used as a background for many of the romantic scenes. ” One Song” a tuneful ballad, is the prince’s love song to Snow White.

” Whistle While You Work ” and ” Isn’t This a Silly Song ” are catchy nonsensical tunes destined for high popular favour.

” Hi-Ho ” is the theme song for the dwarfs. It is a lusty marching tune which they sing in going to and from their work.

” The Wishing Well Song ” and ” With a Smile and a Song ” are ballads.

All of the numbers were written by Frank Churchill and Larry Morey of the Disney music department.

It wasn’t until well into 1933 that the voices for Snow White and the dwarfs were finally decided upon and the detailed preparation of the story was in full swing. Models of the characters, also, were agreed upon-which made possible the beginning of experimental animation.

Over a quarter of a million dollars went into all this preliminary experimental work. The animators had to draw, discard, and re-draw until they arrived at a definite feeling for what actions were right for their characters. Background artists had to experiment until the right effects were evolved.

Actual animation began in 1936, and the cream of Disney’s staff were taken off the short subjects and put to work on Snow White. These included directors, gag men, animators, lay-out men and background artists.

From the outset Disney and his staff realised that colour in the feature would have to be radically different from colour in the ten-minute Silly Symphonies and Mickey Mouses. Thus, colour in Snow White will be subdued and subtle by contrast to the bright pure tones of the short subjects.

There is also a scope for a much wider range of emotions in a feature than there is in a short subject, which naturally means a wider colour range, as colours play an integral part in building up emotional reactions.

In Snow White Disney will not only use colour to explain his characters, but to explain points of the story as well. For instance. Doc and Grumpy, the two most dominant characters among the dwarfs, wear a russet coloured jerkin and a dull magenta one respectively, in contrast to the grey and tan garments of the others. Doc wears the warm russet shade because he is a cheery individual, while the magenta definitely brands Grumpy as an irritable ” wet blanket.” Dopey, the slightly nit-wit member of the little band, wears a ” dopey ” colour scheme of saffron yellow doublet and greyed-lavender cap.

Because Snow White is the star of the piece, she is done in lighter colour values in order that she may stand out against any background. Her skin colouring is light, and the skirt of her gown is cream-coloured.

An example of the part colour plays in the action of the picture is seen in the sequence where the dwarfs discover that someone strange is in their little woodland house. As they cautiously mount the steps to their bedroom, eerie shadow masses of dark blues and blue-greens help to convey to the audience that the little men are sure there is some sort of a monster in the cottage.

When you see the picture in the early part of next year, you will find that, but for a few minor changes, the story clings closely to the Grimms’ fairy tale.

Because of the demands of the motion picture medium, and also because Disney likes to eliminate the gruesome element as much as possible in his productions, the princess Snow White will not have to suffer quite so much at the hands of her wicked stepmother.

In the original tale, she almost died of being laced too tightly by the bad queen, and of having a poisoned comb run through her hair before she finally took a bite of the poisoned apple which finally put her into a bewitched sleep. In the Disney version, the queen only does one dastardly deed in this respect – and that is when she persuades Snow White to bite the apple.

In the original story, the ending finds the wicked queen dying a prolonged death by dancing at the princess’s wedding in red hot iron shoes, all of which is not only blood-curdling reading, but doesn’t make the princess out to be such a ” nice ” girl to permit such things !

In the picture, Snow White isn’t in at the killing and the queen dies more neatly and quickly. The seven dwarfs chase her up and down a hill and dale or two and she topples over a precipice.

And talking of the dwarfs, people who know the famous cartoonist will find something about them that is very familiar – for six of them have his eyebrows.

The Disney eyebrows have fascinated all of his co-workers who have ever sat in story conferences with him, for they wander about – shooting up or cascading down toward the bridge of his nose, helping to create more perfectly any expression Walt may choose to convey.

Therefore, when the dwarfs were being evolved all the artists working on them agreed that no more perfect eyebrows could be wished on them than those resembling Walt’s. Thus, Doc, Sneezy, Dopey, Grumpy, Sleepy and Bashful all have black brows which swoop down or slant up with their varying moods. Happy is the only one who is different. His are white and bushy.

The artists responsible for these quaint and droll little men have become so attached to their brain children that they do not want to see them go into the discard following the making of Snow White.

Although the dwarfs are so likeable and funny that Disney almost weakened for a time, he has come to the definite conclusion that all of the characters in Snow White will have their hour in that picture and never appear again.

” I sincerely believe,” Disney declares, ” that it would be an anti-climax to put them in anything other than the production for which they were created.”

Disney is already beginning work on his second feature, which will be a picturisation of the widely-read book, Bambi, by Felix Salten. It is the story of a deer.

Present plans call for one feature every two years. Walt feels that one a year would be possible but unwise because the quality might suffer.

Above: a scene modelled from Disney’s cartoon figures and, right, models of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs who will make one screen debut and then disappear for ever.

Left: another cleverly modelled scene which reproduces a sequence from the cartoon and, above, Snow White superintends the dwarfs’ diner time. Above : The dwarfs at work. Left and below: further reconstructed scenes from the picture which you will be seeing early in the New Year.

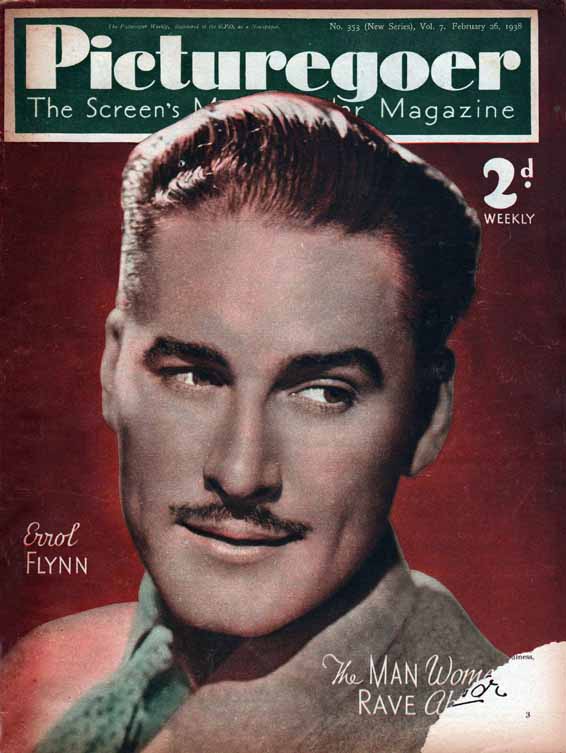

February 26, 1938

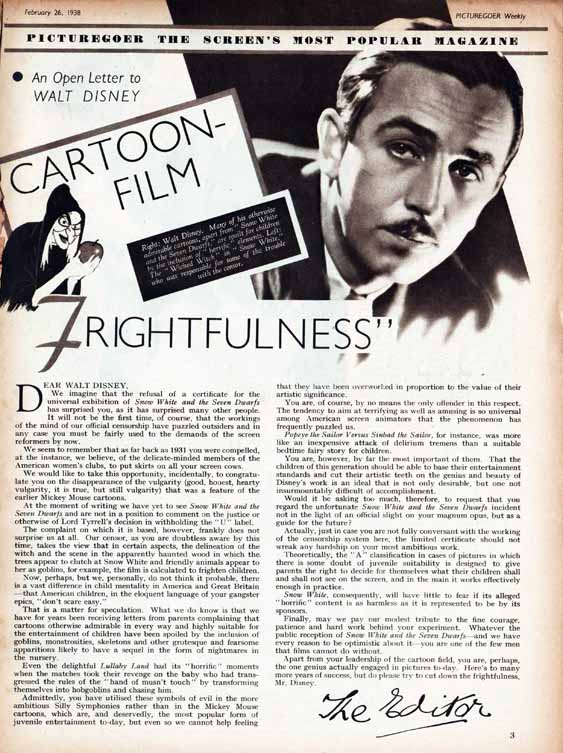

In this issue, the editor wrote an article that reads like a letter to Walt Disney himself, explaining the British point of view regarding the surprising decisions of the censors to give Snow White an “A” rating, meaning that children could not see the picture without their parents. He also begs the producer to remove frighting scenes from future productions. There is also a double page with illustrations of the film. Here is the text.

Cartoon-film Frightfulness

Right: Walt Disney. Many of his otherwise admirable cartoons, apart from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”, are spoilt for children by the inclusion of “horrific” elements. Left: the “Wicked Witch” in “Snow White”, who was responsible for some of the trouble with the censor.

Dear Walt Disney, we imagine that the refusal of a certificate for the universal exhibition of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has surprised you, as it has surprised many other people.

It will not be the first time, of course, that the workings of the mind of our official censorship have puzzled outsiders and in any case you must be fairly used to the demands of the screen reformers by now.

We seem to remember that as far back as 1931 you were compelled, at the instance, we believe, of the delicate-minded members of the American women’s clubs, to put skirts on all your screen cows.

We would like to take this opportunity, incidentally, to congratulate you on the disappearance of the vulgarity (good, honest, hearty vulgarity, it is true, but still vulgarity) that was a feature of the earlier Mickey Mouse cartoons.

At the moment of writing we have yet to see Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and are not in a position to comment on the justice or otherwise of Lord Tyrrell’s decision in withholding the ” U ” label.

The complaint on which it is based, however, frankly does not surprise us at all. Our censor, as you are doubtless aware by this time, takes the view that in certain aspects, the delineation of the witch and the scene in the apparently haunted wood in which the trees appear to clutch at Snow White and friendly animals appear to her as goblins, for example, the film is calculated to frighten children.

Now, perhaps, but we, personally, do not think it probable, there is a vast difference in child mentality in America and Great Britain —that American children, in the eloquent language of your gangster epics, ” don’t scare easy.”

That is a matter for speculation. What we do know is that we have for years been receiving letters from parents complaining that cartoons otherwise admirable in every way and highly suitable for the entertainment of children have been spoiled by the inclusion of goblins, monstrosities, skeletons and other grotesque and fearsome apparitions likely to have a sequel in the form of nightmares in the nursery.

Even the delightful Lullaby Land had its ” horrific ” moments when the matches took their revenge on the baby who had transgressed the rules of the ” hand of musn’t touch ” by transforming themselves into hobgoblins and chasing him.

Admittedly, you have utilised these symbols of evil in the more ambitious Silly Symphonies rather than in the Mickey Mouse cartoons, which are, and deservedly, the most popular form of juvenile entertainment to-day, but even so we cannot help feeling that they have been overworked in proportion to the value of their artistic significance.

You are, of course, by no means the only offender in this respect. The tendency to aim at terrifying as well as amusing is so universal among American screen animators that the phenomenon has frequently puzzled us.

Popeye the Sailor Versus Sinbad the Sailor, for instance, was more like an inexpensive attack of delirium tremens than a suitable bedtime fairy story for children.

You are, however, by far the most important of them. That the children of this generation should be able to base their entertainment standards and cut their artistic teeth on the genius and beauty of Disney’s work is an ideal that is not only desirable, but one not insurmountably difficult of accomplishment.

Would it be asking too much, therefore, to request that you regard the unfortunate Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs incident not in the light of an official slight on your magnum opus, but as a guide for the future ?

Actually, just in case you are not fully conversant with the working of the censorship system here, the limited certificate should not wreak any hardship on your most ambitious work.

Theoretically, the ” A ” classification in cases of pictures in which there is some doubt of juvenile suitability is designed to give parents the right to decide for themselves what their children shall and shall not see on the screen, and in the main it works effectively enough in practice.

Snow White, consequently, will have little to fear if its alleged ” horrific ” content is as harmless as it is represented to be by its sponsors.

Finally, may we pay our modest tribute to the fine courage, patience and hard work behind your experiment. Whatever the public reception of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs—and we have every reason to be optimistic about it—you are one of the few men that films cannot do without.

Apart from your leadership of the cartoon field, you are, perhaps, the one genius actually engaged in pictures to-day. Here’s to many more years of success, but do please try to cut down the frightfulness, Mr. Disney.

The editor

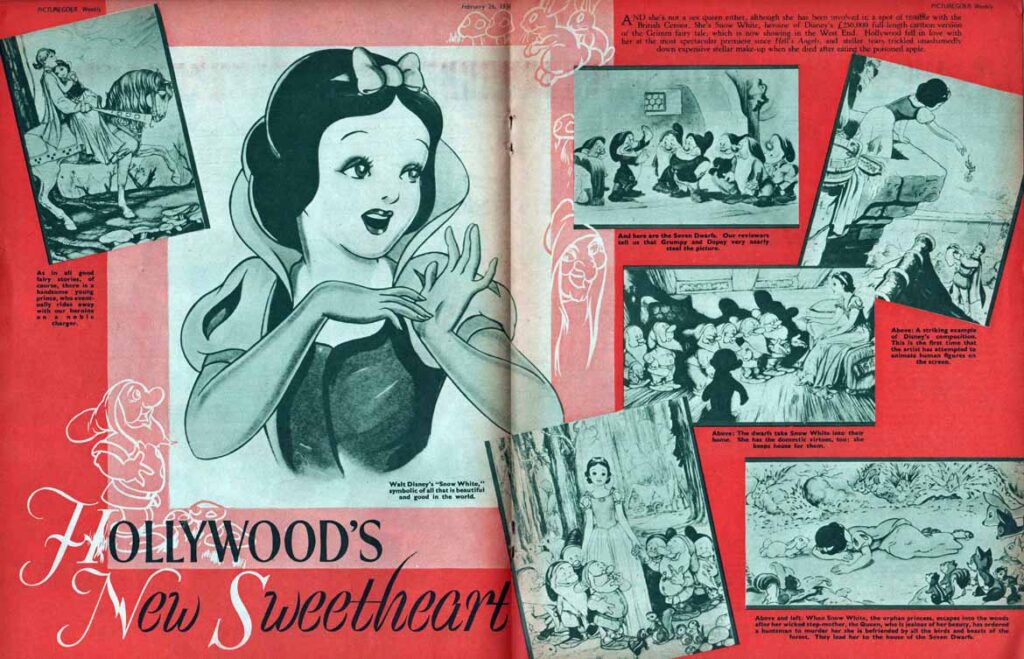

Hollywood’s New Sweetheart

As in all good fairy stories, of course, there is a handsome young prince, who eventually rides away with our heroine on a noble charger.

Walt Disney’s “Snow White”, symbolic of all that is beautiful and good in the world.

And she’s not a sex queen either, although she has been involved in a spot of trouble with the British Censor. She’s Snow White, heroine of Disney’s $250,000 full-length cartoon version of the Grimm fairy tale, which is now showing in the West End. Hollywood fell in love with her at the most spectacular premier since Hell’s Angels, and stellar tears trickled unashamedly down expensive stellar make-up when she died after eating the poisoned apple.

And here are the seven dwarfs. Our reviewers tell us that Grumpy and Dopey very nearly steal the picture.

Above: a striking example of Disney’s composition. This is the first time that the artist has attempted to animate human figures on the screen.

Above: the dwarfs take Snow White into their home. She has the domestic virtues, too; she keeps house for them.

Above and left: when Snow White, the orphan princess, escapes into the woods after her wicked step-mother, the Queen, who is jealous of her beauty, has ordered a huntsman to murder her she is befriended by all the birds and beasts of the forest. They lead her to the house of the seven dwarfs.