Production information

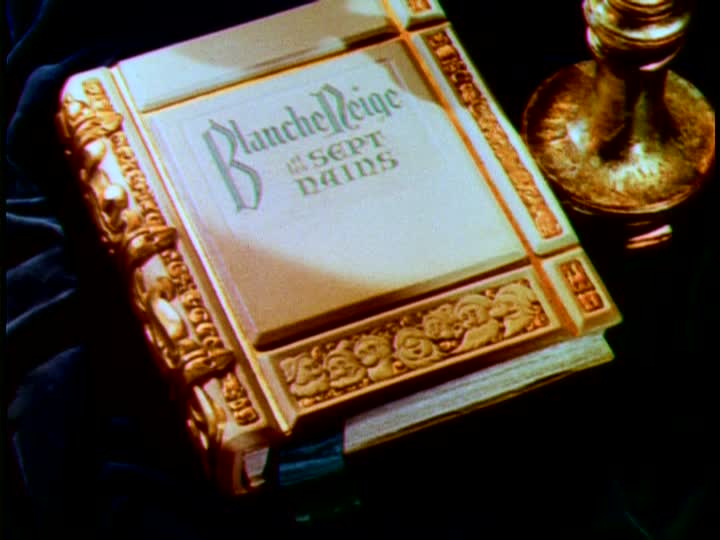

Title: Blanche Neige et les sept nains

General supervisor: Stuart Buchanan

Director: Marcel Ventura

Assistant director: Alfred A. Fatio

Cast

Snow White (dialogs): Christiane Tourneur

Snow White (singing): Beatrice Hagen

The Queen: Adrienne D’Ambricourt

The Prince: Marcel Ventura

The Slave in the Magic Mirror: Jean de Briac

The Huntsman: André Cheron

Doc: Eugene Borden

Grumpy: André Cheron

Happy: Charles de Ravenne

Sleepy: Roger Valmy

Bashful: Louis Mercier

Sneezy: Roger Valmy

First shown in:

May 6, 1938 in Paris, France (Marignan Theater)

May 19, 1938 in Brussels, Belgium (Eldorado Theater)

1938 in Switzerland

Back to Foreign adaptations

A motley crew

For this version Stuart Buchanan recruited a polyglot renowned in Hollywood for his mastery of languages, and his artistic qualities, Mae West’s former Chilean assistant Marcelo Ventura. Prior to that, he had been an embassy attaché in Spain, where he had directed the film “Barcelona Trailer” in his capacity as U.S. delegate to the Barcelona International Exposition. After moving to Hollywood, he appeared as an extra in several of his boss’s films, and had his name changed to Marcel Ventura.

It was he, along with Alfred A. Fatio, would translate the film’s dialogue and songs, and their names can be found on some record sleeves and sheet music, although it’s likely that the lyrics used on these are not those of the film. Marcel used his talents to take on the role of the Prince himself.

The Cast

The roles were then distributed among French or French-speaking actors living in the United States. Director Jacques Tourneur’s wife Christiane Tourneur, née Virideau, an actress with a youthful voice, proved ideal for the lead role. Adrienne d’Ambricourt, a stage and film actress, lends her menacing timbre to the Queen in both her incarnations. The magic mirror speaks thanks to Jean de Briac, who filmed with Mary Pickford in the silent era, then retrained as a French coach for Laurel and Hardy’s French-language films, in which he also played. He continued to play minor roles in numerous Hollywood films until the end of his life.

The huntsman is played by a frequent collaborator of Adrienne d’Ambricourt on screen (he even plays her husband in Artists and Models Abroad): André Cheron. He’s also heard when Grumpy grumbles. Doc has the voice of Eugene Borden, whose round silhouette can be found in a great many films in furtive roles as announcer, doctor, policeman and so on. Borden had been a regular of French versions of Silly Symphonies for years. Happy’s sunny accent was provided by Charles de Ravenne from Nice, who came from a family of actors who had all made a career in Hollywood. Charles was better known as a painter than as an actor, and often confined himself to screen jobs as a bellhop. The deep voice of Louis Mercier, later seen as a policeman in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, is probably that of Bashful.

Roger Valmy may be the voice Sneezy, Sleepy having very little dialogue.

As Christiane Tourneur lacked the singing talent needed to interpret the role of Snow White, the studio hired an American, Beatrice Hagen, a French-speaker who could vocalize the Princess’s mythical songs.

She made the most of her studio contract by singing the role of the farmer’s wife in the Silly Symphony “Farmyard Symphony“. The choice of an American singer and actors whose accents have long since been contaminated by English (Jean de Briac’s is clearly perceptible) is astonishing, as are the anglicisms of a translation done by Francophones rather than French, But this flaw is also found in the Hispanic version, also produced in the USA, where the spoken voice of Snow White is provided by Thelma Boardman, née Hubbard, whose American accent does not mislead for a second as to her origins, and who also performed the role in English on the radio.

Since the studio had decided, as was its custom, to produce the French version on location, it had to make do with local artists.

It should also be remembered that talking pictures were not even 10 years old at the time, and the common use of dubbing was even more recent. Up until 1935, there were still French-speaking films made in America or Germany, with all the accents you can imagine. Dubbing had only recently been adopted as a more economical and viable solution, as it had only recently become technically acceptable. So, while it was obviously not the intention to make song lyrics sometimes unintelligible due to the accent of the performer or the quality of the recording, it was not a totally prohibitive flaw at the time either. At least, that’s how it was judged on its initial release.

The benefits of this version

But let’s leave the shortcomings of this version to focus on its qualities:

First of all, the translation, despite its shortcomings, is often very modern, with respect for the original text and lip-synchronicity, and has the merit of having kept certain elements, not retained in later versions, such as the versified moments outside the songs.

Secondly, the choice of voices is particularly original, especially in view of the constraints that required the French voices to be very close to the originals, which would be heard intermittently for interjections, laughter and other “neutral” sounds. It’s rare, in fact, these days, to choose voices with highly distinctive qualities, so as to forget the dubbing actor’s interpretation behind that of the original comedian. Here, we have Happy with a southern accent, Doc with a nasal timbre to match, a particularly menacing Queen, and a childlike Snow White the likes of whom we’ll never hear again.

The sound editing of this version is also a work of art in its own right, as each version was mixed individually. Indeed, while these days, an international version is prepared with the music and sound effects already mixed, so that all that’s left to do is add the foreign voices, it seems that here, each track has been remixed to suit the needs of each version. Proof of this can be found in the fact that the Queen’s laughter, although systematically retained from the original version, is not mixed in the same place, depending on whether it follows on more or less closely the foreign line. Similarly, Snow White’s cries are more or less numerous in the German, French and Italian versions.

Last but not least, this French version is not limited to a simple sound adaptation. Most shots containing written text have been adapted, re-filmed and, in one case, the scene has been reanimated – a fact unique to the French version. Naturally, the credits were also adapted, and two cards were added, mentioning Buchanan, Ventura and Fatio. The opening book and its first two pages have also been translated. A French-speaking viewer could almost imagine that this was a French film, and that was Walt Disney’s intention.

Release

The first release in France was on May 6, at the Marignan Theater in Paris on the Champs-Elysées where Roy Disney and Stuart Buchanan attended.

It was first shown in Belgium, most likely in a censored version, at the Eldorado In Brussels on May 19, 1938 in presence of the Prime Minister and the American Ambassador.

For the original release, this version was also used in Switzerland, Luxembourg, in all the French colonies and most likely in French speaking regions of Canada.

The American premiere of the French version was at the New York Waldorf Theater on April 8, 1939 where Walt Disney made a personal apppearance.

In December 1944 and January 1945, the film is shown in Paris, Avignon, and possibly in other cities.

It was rereleased in most of these countries in 1951. In 1955, the French version was also illegally used to make black and white subtitled copies for a general release in Russia.

The last general release of this version seems to have been in 1958 in Canada. But extracts were used decades later for TV shows and super 8 films.